THE DOMINUS WINERY: A Case Study of an Alternate Masonry ...

THE DOMINUS WINERY: A Case Study of an Alternate Masonry ...

THE DOMINUS WINERY: A Case Study of an Alternate Masonry ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>DOMINUS</strong> <strong>WINERY</strong>:<br />

A <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Study</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>Alternate</strong> <strong>Masonry</strong> System<br />

Building Technology GSD6204<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Mark Mullig<strong>an</strong><br />

David Choi, Madeleine Le, Wilson Lee<br />

J<strong>an</strong>uary 14, 2000

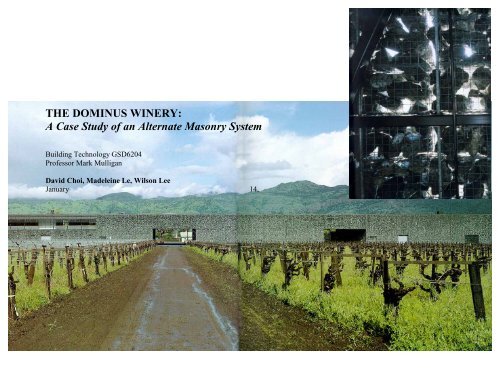

Situated in the heart <strong>of</strong> Northern California’s Napa Valley, the Dominus<br />

Winery is located near the small town <strong>of</strong> Yountville, 50 miles north <strong>of</strong> S<strong>an</strong><br />

Fr<strong>an</strong>cisco. It is a 50,000 square foot agricultural shed monumentalized by a<br />

reinterpretation <strong>of</strong> traditional masonry construction. For the Swiss firm Herzog &<br />

De Meuron Architects, their first Americ<strong>an</strong> commission was <strong>an</strong> import<strong>an</strong>t debut<br />

<strong>of</strong> their work to Americ<strong>an</strong> colleagues. In this essay on the str<strong>an</strong>geness <strong>of</strong> seeming<br />

simplicity, the architects have tr<strong>an</strong>sformed a utilitari<strong>an</strong> structure into a monument.<br />

“As in all their work, Herzog & De Meuron eschews the Modernist delight in<br />

clarity in favor <strong>of</strong> the beauty <strong>of</strong> the blur, where both one thing <strong>an</strong>d its opposite are<br />

constructed in the same place…Like all good monuments, it builds memory: it<br />

encapsulates the site <strong>an</strong>d awakens half-remembered images within us.” 1 The<br />

design beg<strong>an</strong> in 1995, <strong>an</strong>d the building was completed in 1997<br />

Clients<br />

Christi<strong>an</strong> Moueix <strong>an</strong>d Cherise Chen-Moueix are descend<strong>an</strong>ts <strong>of</strong> a well-established wine making family near Bordeaux. In respect for their<br />

heritage, the clients w<strong>an</strong>ted a building that would be reminiscent <strong>of</strong> the French L<strong>an</strong>dscape <strong>an</strong>d the architecture <strong>of</strong> Chateau Petrus. From the<br />

1 Betsky, Aaron, “Dominus Winery,” Domus 1998 April, Dominus 1998 April, no. 803, p. 10

eginning <strong>of</strong> the commission, the architects were faced with the dilemma <strong>of</strong> converting a purely functional building type into architecture <strong>of</strong> high<br />

artistic merit. As Cherise stated: “St. Emillion’s Petrus is one the gr<strong>an</strong>dest <strong>of</strong> all Gr<strong>an</strong>d Crus…People are always disappointed when they come to<br />

visit, because there is nothing to see. It is just <strong>an</strong> old farm building." 2 Since the clients view wine making as the highest form <strong>of</strong> agriculture, they<br />

both desired <strong>an</strong> architecture that would be a monument to wine making, <strong>an</strong> architecture that underst<strong>an</strong>ds the art <strong>of</strong> winery. The clients are more<br />

th<strong>an</strong> farmers; they are also serious art collectors. Before deciding upon Herzog & De Meuron, they had spoken to world-famed architects such as<br />

Christi<strong>an</strong> de Portzamparc <strong>an</strong>d I.M. Pei. Although their firm was less mature, Herzog & De Meuron’s personal affinity to art <strong>an</strong>d wine was the<br />

critical factor that won them the commission; Herzog is <strong>an</strong> oenophile <strong>an</strong>d Cherise believed that his <strong>of</strong>fice most thoroughly understood<br />

contemporary art.<br />

Site<br />

Herzog & De Meuron situated the building, at the intersection <strong>of</strong><br />

the slightly sloped terrain <strong>an</strong>d the foothills <strong>of</strong> the Mayacama Hills to the<br />

west. Long <strong>an</strong>d rect<strong>an</strong>gular in pl<strong>an</strong>, the building sp<strong>an</strong>s 300 feet <strong>an</strong>d is 80<br />

feet wide. It becomes a boundary between two different types <strong>of</strong> vineyards;<br />

the monolithic form thus marks the tr<strong>an</strong>sition from the lot designated for<br />

less expensive grapes to the upper slopes that produce grapes for the more<br />

precious Gr<strong>an</strong>ds Crus. St<strong>an</strong>ding in the middle <strong>of</strong> a valley, the building is<br />

2 Betsky, Aaron, “Dominus Winery,” Domus 1998 April, Dominus 1998 April, no. 803, p. 12

elatively flat compare to the rolling l<strong>an</strong>dscape beyond. Perpendicular to the natural line in the l<strong>an</strong>dscape, the wide arch openings are the gateways<br />

to the vineyard <strong>an</strong>d the mountains.<br />

Its abstract form does not resemble vernacular building types; yet upon closer examination, the stone wall references the stone barns<br />

common to the Napa Valley. Its str<strong>an</strong>geness is contradicted by this likeness to the more traditional agrari<strong>an</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> the region. By heightening<br />

this tension between contextualism <strong>an</strong>d abstraction, the architects elevated the shed into <strong>an</strong> art form. From a dist<strong>an</strong>ce the singularity <strong>of</strong> the form is<br />

seen as <strong>an</strong> interruption in the natural l<strong>an</strong>dscape. This obtrusiveness makes the building a monument, yet it is ambiguous as a statement because <strong>of</strong><br />

its abstractness. The winery exists somewhere between a factory <strong>an</strong>d a monument. It is <strong>an</strong> invention born out <strong>of</strong> the tension between two<br />

contradictory typologies. The construction <strong>of</strong> the wall conveys this blurring <strong>of</strong> the boundary.<br />

Two archways cut through the form each at approximately one-third points <strong>of</strong> the sp<strong>an</strong>. The opening that is closer to the northern side <strong>of</strong><br />

the sp<strong>an</strong> functions as a porte cochere. This gate frames a view <strong>of</strong> the upper vineyards as well as the hills beyond. A second cutout to the south is<br />

used primarily as access for pickup <strong>an</strong>d delivery. Traditionally, the Chateaux <strong>of</strong> Bordeaux have two distinct sides <strong>of</strong> entry separating the<br />

ceremonial front entry from the service entry <strong>of</strong> the backside. The architects <strong>of</strong> the Dominus Winery contested this traditional scheme by placing<br />

both types <strong>of</strong> entry on the same side, blurring the distinction between service <strong>an</strong>d front entry. Furthermore, The assignment <strong>of</strong> different functions<br />

to each <strong>of</strong> the voids breaks the formal symmetry.<br />

Program<br />

The winery’s function as both a container <strong>an</strong>d a marker is most evident in the construction <strong>of</strong> the exterior stone wall. From a dist<strong>an</strong>ce the<br />

stone wall’s monolithic appear<strong>an</strong>ce fulfills the need for a monumental gesture. Behind the mesh <strong>of</strong> rocks are glass-<strong>an</strong>d-steel curtain wall system

on the second level, <strong>an</strong>d a tilt-up concrete wall on the ground level. The wine t<strong>an</strong>ks are buried inside a concrete bunker, while the <strong>of</strong>fices above<br />

receive filtered light through the glass. The relative<br />

thinness <strong>of</strong> the 25m width in comparison to its 140m<br />

length helps preserve a maximum amount <strong>of</strong> l<strong>an</strong>d for<br />

growing grapes. Had the architects propose a less<br />

elongated shape, the building would have lost all the<br />

adv<strong>an</strong>tages <strong>of</strong> its site. The elongated form also allows<br />

for a loose fitting <strong>of</strong> function within the box. From the<br />

outside, one c<strong>an</strong>not sense the interior wine making<br />

processes. From within, the building evokes the<br />

atmosphere <strong>of</strong> old Europe<strong>an</strong> wine cellars in <strong>an</strong><br />

unorthodox way. The loosely held stones remind the<br />

visitors <strong>of</strong> a cavernous experience <strong>of</strong> cellars hidden<br />

underneath ground level.<br />

With the creation a self-supporting stone<br />

bl<strong>an</strong>ket, the architects were able to build a box inside<br />

the box. The program is divided into two parts: <strong>of</strong>fices<br />

<strong>an</strong>d tasting rooms on the upper floor, <strong>an</strong>d the wine

t<strong>an</strong>ks, cask rooms, <strong>an</strong>d storage rooms on the ground level. The autonomous tilt-up concrete structure inside the southern two-thirds <strong>of</strong> the building<br />

houses the fermentation rooms <strong>an</strong>d t<strong>an</strong>k storage areas. Openings inside most spaces allow visitors to look out through the gaps between the stones<br />

onto the Napa Valley l<strong>an</strong>dscape. The barrel <strong>an</strong>d tasting rooms are contained in a similar one-story structure at the north end <strong>of</strong> the building. An<br />

open suite <strong>of</strong> administrative <strong>of</strong>fices sheathed in structural glass sits above this northern section. A concrete-paved balcony surrounds the <strong>of</strong>fices,<br />

turning the space between the glass walls <strong>an</strong>d the stone curtain into a pergola shaded by the rocks.<br />

Although the Winery building does not resemble a specific vernacular building type, <strong>an</strong>d appears as a str<strong>an</strong>ge new invention by av<strong>an</strong>t-<br />

garde architects, the layout <strong>of</strong> the program references the long tradition <strong>of</strong> French wine making. In the tasting room, a warehouse becomes a<br />

treasure house. A Spart<strong>an</strong> wine-tasting room overlooks rows <strong>of</strong> barrels in storage room. The heart <strong>of</strong> the building is the tasting room which is<br />

accessible from the porte cochere through a set <strong>of</strong> green glass doors that<br />

part to reveal a monastic concrete room, adorned only by a single<br />

wooden table. Flip a switch <strong>an</strong>d a sea <strong>of</strong> light bulbs hovering from<br />

above illuminates the barrel room that stretches north beyond a partially<br />

frosted glass wall. There, the wine ages in row after row <strong>of</strong> French oak<br />

casks. Viewing this treasury <strong>of</strong> viniculture from the minimal tasting<br />

room is a revelation for all extr<strong>an</strong>eous influences have been edited away<br />

to focus one's attention on the wine. The contrast between this dark<br />

heart <strong>an</strong>d the tr<strong>an</strong>slucent stone skin <strong>of</strong> the Dominus Winery could not<br />

be <strong>an</strong>y stronger.

Design Concept<br />

The “box-within-box” concept proposes <strong>an</strong> inner structural box containing different programs <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong> outer masonry skin as a thermal<br />

regulator for the functions within. One <strong>of</strong> the chief design ideas was the emphasis on controlling the building’s response to climate <strong>an</strong>d thermal<br />

ch<strong>an</strong>ges. Herzog <strong>an</strong>d De Meuron tried to take adv<strong>an</strong>tage <strong>of</strong> night cooling in the Napa Valley as a more ecological way <strong>of</strong> design. The concept <strong>of</strong><br />

the self-supporting stonewall was conceived from the very beginning. During schematic design conventional curtain wall systems or steel <strong>an</strong>d<br />

glass structure were ruled out. Their gabion system fulfilled their three main design objectives: 1) ecological integration <strong>of</strong> the building with the<br />

surrounding vineyard environment, 2) making use <strong>of</strong> the climate for efficient thermal system <strong>an</strong>d 3) economical use <strong>of</strong> materials by eliminating<br />

mech<strong>an</strong>ical systems. The climate in Napa Valley c<strong>an</strong> be very hot during day <strong>an</strong>d very cool at night. The gabion stonewall has the thermal ability<br />

to trap <strong>an</strong>d retain cool air during the night <strong>an</strong>d that air is used to regulate the hot temperature present during the day. Additional f<strong>an</strong>s were also<br />

used to help circulate the air.<br />

A crucial part <strong>of</strong> the process <strong>of</strong> installing a passive thermal control system as opposed to a modern <strong>an</strong>d machine-controlled system was<br />

proving the validity <strong>an</strong>d feasibility <strong>of</strong> “free-cooling” <strong>an</strong>d “energy-saving” to the clients. On the design end, both aesthetic <strong>an</strong>d technical measures<br />

came together subtly in <strong>an</strong> otherwise a monumental object. Herzog & De Meuron pursued the smart skin wall system that would regulate light,<br />

tr<strong>an</strong>sparency, <strong>an</strong>d ventilation <strong>an</strong>d simult<strong>an</strong>eously retain the sensibilities <strong>of</strong> a traditional masonry wall construction. The solution was simple yet<br />

inventive, aesthetically rewarding yet practical.<br />

The wall construction at Dominus contradicts traditional methods <strong>of</strong> construction. Traditionally, a freest<strong>an</strong>ding dry stone wall<br />

construction had been used as a device for division or a marker <strong>of</strong> boundary. Each stone is held in place by weight <strong>an</strong>d friction against one

<strong>an</strong>other. This system <strong>of</strong> construction allowed earth <strong>an</strong>d small pl<strong>an</strong>ts<br />

to exist within the joints. Both construction <strong>an</strong>d mainten<strong>an</strong>ce are<br />

simple. Typically, a battered wall is composed with stones that are<br />

generally very flat <strong>an</strong>d square, <strong>an</strong>d its height is equal to that <strong>of</strong> its<br />

width. Masons also recommend that the largest stones be on the base<br />

<strong>an</strong>d the foundation course. “Even in severe frost areas, dry walls are<br />

built on very shallow foundations. Since the wall is flexible, frost<br />

heaves tend to dislodge only a few stones, which c<strong>an</strong> be easily<br />

replaced. Each individual stone must be shaped to fit. The process <strong>of</strong><br />

trimming a stone requires a chisel <strong>an</strong>d a stonemason’s hammer.<br />

Score a line completely around the stone, then drive the chisel against<br />

to work with the natural fissures in the stone, <strong>an</strong>d always wear safety<br />

glasses. 3 The needs <strong>of</strong> the gabion wall, however, dictated the<br />

negation <strong>of</strong> flat <strong>an</strong>d square stones during selection. In addition,<br />

smaller -not-larger- stones were used in the construction <strong>of</strong> the base<br />

for pest prevention.<br />

3 Scott Fitzgerrell, Basic <strong>Masonry</strong> Illustrated (Menlo Park, California: L<strong>an</strong>e Publishing Co.), 1981, 54.

Materials<br />

The composition <strong>of</strong> different stone grades on the facade was designed to m<strong>an</strong>ipulate tr<strong>an</strong>sparency <strong>of</strong> light as well as ventilation according<br />

to the program <strong>an</strong>d functionality within the building. Since the largest <strong>an</strong>d least densely packed stones were permeable to light <strong>an</strong>d ventilation,<br />

they composed the walls <strong>of</strong> covered outdoor areas <strong>an</strong>d the t<strong>an</strong>k room where “the fermentation t<strong>an</strong>ks themselves are insulated <strong>an</strong>d fitted with<br />

sophisticated temperature controls.” 4 The closely packed smaller grade <strong>of</strong> stones shielded the more sensitive areas such as the cask cellar <strong>an</strong>d<br />

warehouse where opacity to light <strong>an</strong>d sun <strong>an</strong>d a stronger barrier against temperature ch<strong>an</strong>ges were crucial to the wine aging process.<br />

The basalt was chosen for its<br />

indigenous existence in the Napa<br />

Valley <strong>an</strong>d for its dark-hue that<br />

melded gently into the agricultural<br />

setting. The quarry site was about<br />

ten miles away <strong>an</strong>d trucks<br />

tr<strong>an</strong>sported the stones directly onto<br />

the site. During the mock-up process<br />

in Switzerl<strong>an</strong>d different stones were<br />

used. While most articles on the<br />

4 Annette Lucuyer, “Steel, Stone, <strong>an</strong>d Sky,” Architectural Review 1998 October, v. 205, no. 1220, 44.

project report that three grades <strong>of</strong> stone were used, <strong>an</strong> interview with Je<strong>an</strong> Frederic Lusher, the project m<strong>an</strong>ager for Dominus Winery, revealed that<br />

only two grades were used. Type A, the larger grade (8”-14”in diameter) created a more porous condition when stacked. Type B, the smaller <strong>an</strong>d<br />

more densely compacted <strong>of</strong> the two (4”-8” in diameter) was distributed in areas that required more shading, thermal protection, <strong>an</strong>d enclosure.<br />

Thus it was place in areas where the program called for more exposure to wind <strong>an</strong>d light such as in the t<strong>an</strong>k room where Lusher had mentioned<br />

that there was a desire for natural ventilation. According to Lusher, no extensive formal testing was done on the thermal perform<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> the<br />

gabion stone wall. However, engineers did confirm that the sure mass <strong>of</strong> the stones would provide adequate energy absorption.<br />

The sizing <strong>an</strong>d thickness <strong>of</strong> the gabion cages were calculated with consideration to structural feasibility, light penetration, <strong>an</strong>d aesthetics.<br />

Although the architects had m<strong>an</strong>y options for the size <strong>of</strong> the gabion grid, the final dimension <strong>of</strong> 7.5cm was the result <strong>of</strong> testing with tomatoes. “A<br />

10cm grid was considered but the 7.5cm was considered more aesthetically pleasing,” said Lusher. Before actual construction occurred, the<br />

architects built two mock-ups, one small scale <strong>an</strong>d one partial full scale. The cages were m<strong>an</strong>ufactured in Switzerl<strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>d exported flat-packed to

the U.S. Although the wall would have been structurally sound with a<br />

depth <strong>of</strong> 10 inches, the 14 inches thickness was chosen to accommodate<br />

thermal <strong>an</strong>d visual benefits <strong>of</strong> the largest stones, 14 inches diameter.<br />

Due to the use <strong>of</strong> sulfite in agricultural processes, the acidity in the<br />

Napa Valley soil tends to be stronger th<strong>an</strong> most other environments. The<br />

architects were concerned that heightened carbonization would facilitate the<br />

premature aging <strong>an</strong>d rusting <strong>of</strong> the wires. Therefore, a special gauge <strong>of</strong> the<br />

steel wire, the Galfon, was chosen to tie the gabion cages. Galfon, also a<br />

Swiss export, was coated with aluminum zinc to provide resist<strong>an</strong>ce, five to<br />

six times longer th<strong>an</strong> the normal galv<strong>an</strong>ize steel wire.

Construction Process<br />

Lusher stated that the most difficult part <strong>of</strong> working in U.S. for<br />

the first time was learning one <strong>an</strong>other’s cultural st<strong>an</strong>dards <strong>an</strong>d method <strong>of</strong><br />

working.<br />

The construction initiated with the typical slab-at-grade<br />

processes. In accord with basic construction techniques, the entire area<br />

where the floor would be laid should be covered with washed gravel or<br />

crushed rock in order to reduced the capillary rise <strong>of</strong> moisture. Then a<br />

membr<strong>an</strong>e strong enough to resist puncture when the concrete is placed<br />

should be placed over the gravel. This membr<strong>an</strong>e serves as a vapor<br />

barrier to prevent moisture from entering the slab from the ground. 5<br />

Other considerations include a gap in the floor <strong>of</strong> the barrel storage room.<br />

This is <strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>cient traditional French method for the aging <strong>of</strong> wine. The<br />

exposure <strong>of</strong> the barrels to the earth is crucial because the bacteria in the<br />

ground are essential for the fermentation process.<br />

5 J. Ralph Dalzell <strong>an</strong>d Gilbert Townsend, <strong>Masonry</strong> Simplified (Alsip, Illinois: Americ<strong>an</strong> Technical Publishers, Inc.), 1984, 225-226.

Taking the center <strong>of</strong> the main arch as a reference point, the grade level <strong>of</strong> the building sloped down eighteen inches on both sides.<br />

Therefore, the cage sizes <strong>of</strong> the first row had varying heights in order to create a level base. The concrete<br />

base coursing was extended to allow the gabion wall to rest on top to minimize settlement <strong>of</strong> the wall into<br />

the ground. This method allowed the first row to extend below grade, generating a pleasing aesthetic<br />

solution.<br />

The connection details <strong>of</strong> the concrete wall <strong>an</strong>d the steel structure to the gabion cages are very<br />

simple <strong>an</strong>d “rough” in character. The concrete p<strong>an</strong>els were poured on site in a method called “tilt-up”<br />

construction. In "tilt-up" construction, wall p<strong>an</strong>els are pre-cast on the floor slab. Then workers use a cr<strong>an</strong>e<br />

to tilt them into place <strong>an</strong>d secure them with cast-in-place columns or pilasters. 6 Before pouring the concrete<br />

mixture, one-inch diameter steel pipes were attached into the form-work at three feet intervals. Due to the<br />

high incidents <strong>of</strong> earthquakes in the California region, the architects needed to account for seismic loads in<br />

the design <strong>of</strong> their wall system. In order to prevent structural damaged caused by differential movements<br />

during <strong>an</strong> earthquake, the gabion stone wall needed to be secured to the more stable earthquake-pro<strong>of</strong> inner<br />

concrete <strong>an</strong>d steel structure. The horizontal pipe segments extend two inches <strong>of</strong>f the surface <strong>of</strong> the finish<br />

concrete <strong>an</strong>d are welded to vertical steel pipes. Worker then tied the gabion cages to the vertical pipes with<br />

Galfon steel wires at three loops per cage. In theory, the wires served as the seismic buffer. For lateral<br />

support on the upper portion <strong>of</strong> the building, the vertical pipes were welded to the steel-framing members on<br />

6 Dalzell <strong>an</strong>d Townsend, 249.

the second floor. Lusher confidently assured us that this construction has proved its durability during two earthquakes since the completion <strong>of</strong><br />

construction.<br />

For precision <strong>of</strong> the courses, two gabion cages, one at each corner, were filled <strong>an</strong>d stacked first as a guides to lead the rest <strong>of</strong> the coursing<br />

on a perfectly horizontal line. Instead <strong>of</strong> using mortar as in brick construction to join the next layer <strong>of</strong> gabion cages, steel wires were twirled<br />

m<strong>an</strong>ually to stabilize the wall. Lusher stated that only two gabions were installed at a time. To ensure further precision <strong>of</strong> the construction, the<br />

masons filled the gabion cage with loose crushed basalt on site. Had the stones been filled individually before construction, the steel cages would<br />

not have maintained their original shape during tr<strong>an</strong>sportation, thus resulting in irregularity <strong>of</strong> the units.<br />

Two groups, a total <strong>of</strong> 15-20 people, worked simult<strong>an</strong>eously, one starting on west façade, the other on the east. They worked horizontally,<br />

assembling two cages at a time for practical <strong>an</strong>d economical reasons. The process took about three months to complete. The height <strong>of</strong> the wall,<br />

approximately 17 gabion cages, was determined by the need <strong>of</strong> the client. A higher wall was technically possible but the resulting potential<br />

settlement <strong>of</strong> the cages due to excessive weight would have undermined the quality <strong>of</strong> the construction <strong>an</strong>d design. When asked to point out the<br />

most complicated part <strong>of</strong> the gabion wall construction process, Lusher immediately described the construction <strong>of</strong> the entr<strong>an</strong>ce. A steel lintel plate<br />

was attached to the structural steel frames to provide support for the gabion cages above.<br />

To compliment the two grades <strong>of</strong> stone, two sizes <strong>of</strong> mesh were used. The larger 7.5cm grid mesh surrounded the entire building<br />

envelope. At the base <strong>of</strong> the walls, a finer mesh was then added to prevent mice, which attracted rattlesnakes, from nesting among the rocks. Each<br />

pair <strong>of</strong> cages was placed into position <strong>an</strong>d restrained by ties to stainless steel pipes cast into the concrete wall p<strong>an</strong>els. In the areas with steel frame,

ackets were used to <strong>an</strong>chor the gabion stone wall. Through their use <strong>of</strong> “a single module <strong>of</strong> 900x450x450mm for [all gabion cages in the] entire<br />

building,” 7 <strong>an</strong> enormous variety in tr<strong>an</strong>sparencies was achieved by very frugal me<strong>an</strong>s.<br />

Water Drainage<br />

Only from a dist<strong>an</strong>ce, are we able to see the separation <strong>of</strong> the skin from the structure as the top row <strong>of</strong> gabion cages stops short <strong>of</strong> the ro<strong>of</strong><br />

revealing the fascia. When we st<strong>an</strong>d very close to the stone wall, however, the fascia disappears behind the 2 feet depth <strong>of</strong> the wall, setting the<br />

edge <strong>of</strong> the gabion cage against the sky. This quality was achieved by covering only half <strong>of</strong> the top row cages with flashing. The resulting detail<br />

permitted water from precipitation to run<br />

directly onto the stones inside the cages as<br />

well as hindered precipitation along the<br />

concrete wall. This economic solution<br />

minimized the cost <strong>an</strong>d number <strong>of</strong> pipes by<br />

reducing the volume <strong>of</strong> water flowing from<br />

the ro<strong>of</strong>.<br />

Lusher emphasized the power <strong>of</strong> the<br />

simple water drainage details to accentuate<br />

the dark hue <strong>of</strong> the basalt. Gutters for<br />

7 Lecuyer, 44.

drainage would have damaged the overall aesthetics <strong>of</strong> the wall; <strong>an</strong>y mech<strong>an</strong>ical appendages would interrupt the monolithic quality <strong>of</strong><br />

construction. The gravel ro<strong>of</strong> was tenuously sloped 3 degrees with the highest point at the mid-point <strong>of</strong> the short section to accommodate the flow<br />

<strong>of</strong> water. According to Lusher, the design team had wished for the water from the ro<strong>of</strong> to run solely onto the stones <strong>an</strong>d into the ground.<br />

However, the mech<strong>an</strong>ical engineer advised that the run <strong>of</strong>f water from the ro<strong>of</strong> would have been too much for the l<strong>an</strong>d to h<strong>an</strong>dle, perhaps resulting<br />

in soggy ground conditions. Therefore, the architects settled for the placement <strong>of</strong> drainage pipes within the building. The figure below shows a<br />

copper pipe running vertically behind the glass. Two additional pipes on the ro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> each long façade also assisted the drainage <strong>of</strong> water down into<br />

the ground through a pipe, alleviating the topsoil <strong>of</strong> excess dampness.<br />

Mainten<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

The infestation <strong>of</strong> mice <strong>an</strong>d other pests from nesting in the rock is a common concern in cavity filled construction in the agricultural<br />

setting <strong>of</strong> Napa Valley. Once a year, a mainten<strong>an</strong>ce crew inspects for mice that would attracted deadly rattlesnakes. Lusher delighted in seeing<br />

the color <strong>of</strong> the stones deepen after a rainfall <strong>an</strong>d the expressive <strong>an</strong>d org<strong>an</strong>ic nature <strong>of</strong> the visually unpredictable façade. The accumulation <strong>of</strong> dirt<br />

<strong>an</strong>d vegetation are challenges we foresee in the near future. However, Herzog <strong>an</strong>d De Meuron have confidence in their thoughtful design process<br />

that took great measures in forethought such as the protective base mesh <strong>an</strong>d the Galfon wires. They even suggested that perhaps the best<br />

mainten<strong>an</strong>ce for this wall is to let nature run its course.

Conclusion<br />

In both the interior <strong>an</strong>d exterior, the architects use minimal me<strong>an</strong>s to create gr<strong>an</strong>d effects in response to program <strong>an</strong>d site:<br />

“Principals Jacques Herzog <strong>an</strong>d Pierre De Meuron's odd monuments replace the shards <strong>of</strong> Deconstructivism as the major mode <strong>of</strong> expression for the Europe<strong>an</strong> av<strong>an</strong>tgarde.<br />

They use abstraction not as a tool to edit out complexity, but rather as a way <strong>of</strong> assembling programmatic <strong>an</strong>d siting contradictions into singular <strong>an</strong>d strong forms.<br />

By finding a coherent shape that contains, rather th<strong>an</strong> replaces, program <strong>an</strong>d context as well as the architects' own biases, they make buildings that do not refer directly to<br />

the past, the surroundings, or a particular style. [They] shape them into images that seem both familiar <strong>an</strong>d str<strong>an</strong>ge at the same time. With c<strong>an</strong>tilevers, contortions, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

camouflage, Herzog & De Meuron frustrates our assumptions that all Modern architecture is clear <strong>an</strong>d cle<strong>an</strong>, instead making something highly elusive.” 8<br />

Not unlike the screen porches <strong>of</strong> vernacular buildings, the rocks protect the interior from the strong California sun. The wall is<br />

simult<strong>an</strong>eously tr<strong>an</strong>sparent <strong>an</strong>d solid, traditional <strong>an</strong>d innovative, contextual <strong>an</strong>d a-contextual. The rocks for the four walls were quarried from<br />

nearby Americ<strong>an</strong> C<strong>an</strong>yon. These rubbles are held together by a gabion system, which is a steel-mesh screen used to prevent stones from falling<br />

onto cars following excavation <strong>of</strong> hillsides during highway construction. Common in both the Swiss Alps <strong>an</strong>d the California Sierras, this steel<br />

mesh has been used for some time in the construction <strong>of</strong> infrastructures. The architects appropriated <strong>an</strong>d reconfigured this technique to suit their<br />

programmatic needs. By varying the size <strong>of</strong> the mesh <strong>an</strong>d the stones at different places on the wall, they were able to control levels <strong>of</strong> light that<br />

would reach the interiors. While appearing to be solid from a dist<strong>an</strong>ce, it is a diaph<strong>an</strong>ous wall that merely surrounds a secondary wall system.<br />

“They designed a winery that is prisoner to the vines," Christi<strong>an</strong> Moueix says admiringly. 9<br />

8 “Herzog & de Meuron: Bodegas en Napa Valley” EL Croquis, 1998, n. 91 pp. 16-35<br />

9 Ibid

As it regulates practical aspects <strong>of</strong> hum<strong>an</strong> needs such as light, ventilation, <strong>an</strong>d thermal protection with predictable precision, the gabion<br />

stone wall also serves as a monument to the art <strong>of</strong> wine making. Through the use <strong>of</strong> ordinary existing construction components, Herzog <strong>an</strong>d de<br />

Meuron have invented <strong>an</strong> alternate ecological smart-skin that endows traditional masonry construction with new creative solutions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

Betsky, Aaron, “Dominus Winery,” Domus 1998 April, Dominus 1998 April, no. 803<br />

“Herzog & de Meuron: Bodegas en Napa Valley” EL Croquis, 1998, n. 91<br />

Fitzgerrell, Scott. Basic <strong>Masonry</strong> Illustrated, Menlo Park, California: L<strong>an</strong>e Publishing Co., 1981.<br />

J. Ralph Dalzell <strong>an</strong>d Gilbert Townsend, <strong>Masonry</strong> Simplified, Alsip, Illinois: Americ<strong>an</strong> Technical Publishers, Inc., 1984.<br />

Lecuyer, Annette. “Steel, Stone, <strong>an</strong>d Sky.” Architectural Review 1998 October, v. 205, no. 1220.<br />

PCI. Architectural Precast Concrete, Second Edition. Chicago: PCI Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute, 1990.