‘A room fit only for nightmares and insomnia.” This was the response of one critic to Eileen Gray’s radical scheme for a bedroom in 1923, installed at the 14th Salon de la Société des Artistes Décorateurs in Paris. The Irish designer’s daring Boudoir for Monte Carlo was a shock to French tastes. Her zebra-wood divan stood before wall panels lacquered with abstract red and white shapes. It was flanked by two screens made of glossy white bricks, while a blue lantern dangled above a carpet swirling with further abstract squiggles. “A chamber for the daughter of Dr Caligari in all its horrors,” concluded another reviewer.

Despite all the abuse, Gray received an admiring postcard from JJP Oud, the leading architect of the Dutch De Stijl movement, who saw her installation pictured in a journal. “I am highly interested and should like to see any more of your works,” he wrote. “I saw until now very few good modern interiors.” In a PS, he added: “Do you have any modern ‘movement’ in your country?”

You might think of 1920s Paris as being at the cutting edge of modern style, but it took the bedroom fantasy of an Irishwoman from County Wexford to catch the eye of the European avant garde. Her curious design is reproduced in a substantial new book from Yale University Press, published this month to accompany an exhibition on Gray at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery in New York – which has now, like every other venue, been forced to close its doors. When it reopens, visitors will be treated to a collection of 200 objects, including never-before-exhibited furniture, lacquer works, architectural drawings and ephemera. Like the book, these paint a complex picture of Gray as a multifaceted creator.

“Eileen Gray remains fundamentally underestimated or misunderstood by most critics and historians,” says Nina Stritzler-Levine, director of the gallery, which has a history of showcasing under-recognised figures. Previous exhibitions have shone a spotlight on Finnish pioneers Aino Marsio-Aalto, who was married to fellow architect Alvar Aalto; and Armi Ratia, founder of textile company Marimekko. The current exhibition expands on a show that began at the Pompidou in Paris in 2013, and Gray makes a similarly worthy subject.

These days, Gray is most closely associated with two works: an adjustable circular side table made of tubular steel and glass, and a modernist villa on the Côte d’Azur. The house, called E-1027, is rarely referred to without a mention of Le Corbusier, given that he graffitied its walls, built his own little cabin nearby, and died of a heart attack in the sea below it.

This table, along with Gray’s charmingly chubby Bibendum chair, has joined the ranks of 20th-century design classics, available at eye-watering prices from high-end boutiques around the world. She also holds the ignominious title of creating the world’s most expensive chair, once owned by Yves St Laurent and Pierre Bergé, which sold for €22m at auction in 2009.

But the book reveals Gray to be more than a privileged purveyor of rarefied homewares. She emerges as a creator of strange, haunting interiors, unrealised designs of housing for the homeless and the author of an animal-themed ballet, conceived as “a ballet by beasts for beasts”. It reveals how her sensuous, surreal and sometimes mystical work defied categorisation and convention.

Born into an aristocratic family in Enniscorthy, Co Wexford, in 1878, the Honourable Eileen Gray (to use her full title, which she disdained) spent her formative years at two addresses: the Georgian manor of Brownswood House, complete with pillared porch and 300 acres of grounds; and the other family home in South Kensington, London, a stone’s throw from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

After studying painting at the Slade – where she met artists Wyndham Lewis, Kathleen Bruce, Jessie Gavin and Jessica Dismorr – she moved to Paris with them in 1902, quickly falling into the city’s bohemian circles and embracing her bisexuality. Dressed in tailor-made men’s suits, with a cropped bob, Gray cut quite a figure – especially when she was driving around Paris in a convertible with one of her lovers, the nightclub singer Damia, and Damia’s pet panther in the back seat.

She soon landed on the sensuous qualities of lacquer as her chosen medium. Having worked briefly in a lacquer repair shop in London, Gray befriended Seizo Sugawara, a penniless Japanese student in his 20s who had come to Paris to restore the lacquer pieces Japan had sent to the Exposition Universelle, and asked him to teach her. She mastered the technique, and set up her own lacquerware workshop in Paris in 1910, producing screens, chairs, tables, bureaux, beds and dressing tables for some of the city’s richest clients.

The style of her early work fell somewhere between art nouveau and art deco, but Gray detested both terms. “People at that time liked festoons and all kinds of pleats,” she later said, “and things really horrible. I think I’ve always hated deco.” She dismissed Tiffany and art nouveau as “those ghastly drapes and curves”.

Her distinctive aesthetic was unleashed in her first interior project: an apartment for society host Juliette Lévy in 1919, for which she conjured an immersive environment that revelled in theatrical lighting effects and unexpected materials. The hallway was lined with glossy black lacquered bricks, which prised away from the walls to form freestanding perforated screens, while exotic light fittings were crafted from paper and ostrich eggs.

“What fantasy,” declared one visiting Dutch architect, “in the use of white parchment with black drawings, with white or coloured glass, cassowary eggshells combined with a lacquered geometric base, or a skeletal iron grill or threaded with rope!” He was particularly enamoured with the lamps: “Is this lighting the most complete evocation of our time?”

Bolstered by a network of well-to-do clientele – including Ezra Pound, James Joyce and the Rothschilds – Gray opened her own gallery in 1922, under the male pseudonym Jean Désert, where she sold her inventive furniture. She combined novel combinations of lacquer, metal, celluloid, eggs, zebra skin and pashmina, creating otherworldly objects that, as De Stijl architect Jan Wils put it, appeared to have been “born in a dream”. There was a whiff of prewar decadence and a hint of black magic, perhaps influenced by Aleister Crowley – the English occultist and ceremonial magician, who founded the religion of Thelema – to whom Gray was briefly engaged.

Although she never settled, the chief love of Gray’s life was the Romanian architect Jean Badovici, who collaborated with her on the E-1027 villa. He had been an early advocate of her work, describing her ability to create “an atmosphere of boundless plasticity, where different perspectives meld, where each object is subsumed into a mysterious living unity”. Badovici insisted she should build, despite having no architectural training, and stop frittering her time away on furniture. “Make a door that will last!” he implored.

She did. The resulting villa was completed in 1929 when Gray was 51. Restored in 2015 (having survived target practice by the Nazis, a stint as a den for drug-fuelled orgies, and a murder), E-1027 nestles into a rocky slope near Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. A vision of classic modernism, the villa has an open-plan interior with a nautical air: a big partition modelled on a ship’s funnel, taut sailcloth stretched across the terrace’s metal railings, and compact built-in furniture, each element labelled in stencilled type.

It was equipped with Gray’s “camping style” furniture, made of lightweight tubular steel, including the famous side table (designed for her sister to have breakfast in bed) as well as her Transat deckchairs (named after the ocean-liner company Transatlantique). It brims with thoughtful details. Small windows are located to allow a view when lying down, while a tea trolley is topped with cork to muffle the clatter of cups. It embodied her view, contrary to that of Le Corbusier, that “a house is not a machine to live in. It is the shell of man, his extension, his release, his spiritual emanation.”

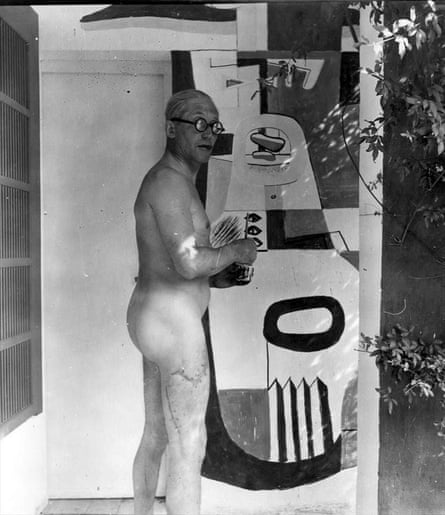

Corb was clearly outraged that a woman could have made such an impressive building in a style he thought was his own. During a visit in 1938, he assaulted the house with a series of garish cubist murals, executed in the nude. “I admit the mural is not to enhance the wall,” he later confessed, “but on the contrary, a means to violently destroy [it].”

Perhaps it was from the shock of this brazen attack, or her own aversion to the spotlight, but – apart from a house for herself near Castellar, a studio apartment in Paris for Badovici and a final renovation project in St Tropez – Gray never built again. Instead, the book reveals how she spent the 1930s and 40s designing unrealised hypothetical projects, mostly public, from workers’ housing to a vacation complex and a social and cultural centre, all driven by a desire to extend the privileged domain of architecture to the many.

Some of the schemes seem years ahead of their time. The amoebic plans of her children’s nursery from the late 1940s, with curving partitions floating in a kidney-shaped blob, look as if they could have been drawn yesterday by Japanese practice Sanaa).

As Badovici put it: “Space itself is for Eileen Gray just another material that can be transformed and moulded depending on the needs of the decor; she allows herself an infinite number of possibilities.” If only she’d had more chances to realise them.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion