Japanese Architecture: A Visit to Some Typical Buildings

by MOSUKE MORITA

1

INTEREST in Japanese architecture seems to be steadily rising in the United States. American architectural periodicals show an increasing impact of Japanese influence. The Japanese “Pine Breeze House” set up in the garden of the Museum of Modern Art in New York has fascinated tens of thousands. Recently I was asked by a GI, who had been sent to Japan just after his graduation from an architectural school, to show him some representative examples of our architecture. Perhaps you readers would enjoy a similar sight-seeing tour. Let us start with a modern building, the Hasshokan inn and restaurant in Nagoya.

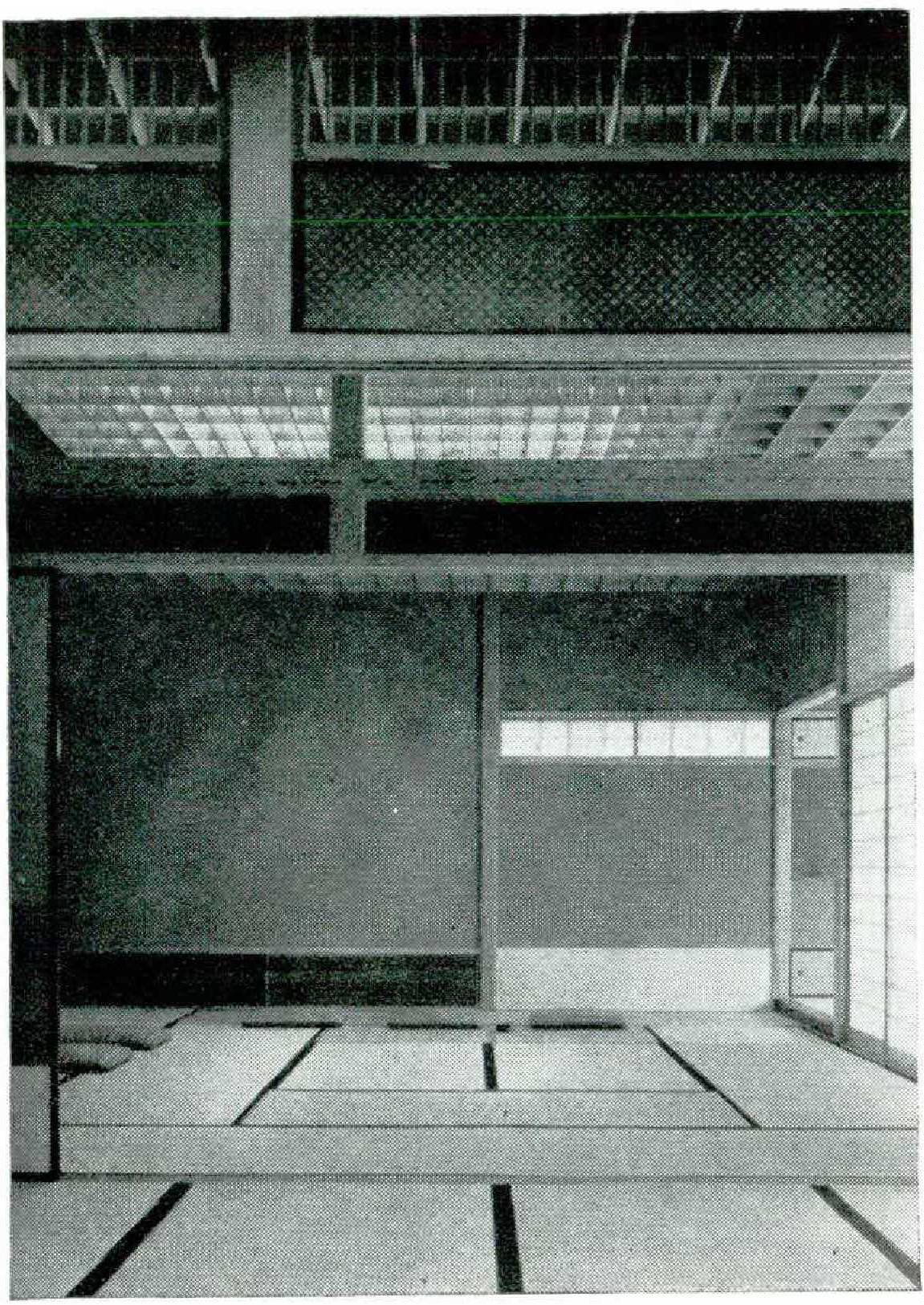

Plates 1 and 2 in our picture section show one of the rooms of this restaurant, designed by the architect Sutemi Horiguchi. It represents traditional style brought up to date by air conditioning and certain radical innovations. Posts and beams of plain wood, rush mats, and sliding doors are traditional, while glazing in the doors, fluorescent lamps, and the color-patterning of walls and ceilings in a Mondrian-like style are modern. The novel latticework of plain cypress wood on the ceiling is backed with colored papers—vermilion, ultramarine, viridian — and conceals the lamps and the air conditioning.

As in every Japanese house, you leave your shoes behind in the entrance hall, put on a pair of guest slippers, and are now invited to crouch on silken cushions placed on rush mats. The Japanese do not use chairs or bedsteads, and all living takes place on the floor. You notice that it is wholly covcred with these mats, twenty-four of them, each exactly three feet by six. Not only these measurements but those of the sliding doors and all other architectural components are fixed according to a traditional module, making them interchangeable.

While you are waiting for your dinner and looking about, you may express surprise at the room’s bareness and the absence of pictures or other decoration. In this the restaurant is not unusual: such things as screens, tables, boxes, bureaus, and bedding are kept in storage except at the time of use; and as for pictures, it is believed universally in Japan that, the effect of works of art is much greater if only one is seen at a time, and that one intently and at length, usually in a niche of honor, called the tokonoma, which had its origin in the alcove dedicated to Buddhist deities in warriors’ homes. Even collectors who have hundreds of pictures keep all but a few stored.

Looking at the garden through an opening so wide that house and garden seem to he one, you become aware of that most fundamental Japanese architectural conception: between house and garden there must exist an organic unity. Observe how meticulous is the grooming of the trees and plants. Notice also that there are no large beds of flowers, as in European gardens, but only bits of color for accent, and that stones and path designs play an important part in the composition. Because we think of our gardens as works of art, they arc more often designed to he viewed from the house and its verandas than to be sat in. Later we shall examine more elaborate gardens.

And now, as you are beginning to wonder how your Japanese host crouches so easily on his cushion, the waitresses bring the food. On the mat floor before each person is set a lacquer tray, with little legs. Or sometimes a very low table will be used instead. You are sure to be struck by the purely visual beauty of the multicolored and multishaped delicacies. Perhaps the rich variety of the ware will also surprise you. Your raw fish is on a flat oblong dish, with white and red pieces of meat arranged decoratively on the bed of snow-white radish sliced to the thinness of thread. Orange carrots have been cut to look like tiny flowers. Your vinegared green vegetables are in that deep dish. The gold-lacquered bowl with the tight-fitting lid contains your clear soup. The whole is a little work of art, and you will not be surprised to learn that some restaurants pride themselves on using dishes which are almost museum pieces. We say that Chinese food is best for taste, French for savor, and Japanese for looks. But do not fear that its decorativeness makes it any less delicious.

When the trays of colorful dishes are cleared away, the room again takes on its chaste appearance. This is not limited to this restaurant, but is a universal characteristic of Japanese architecture. Rooms are not specifically for dining or sleeping or receiving guests: all are interchangeable. This dining room could become a bedroom simply by spreading bedclothes on the floor. Our thick quilts are soft enough without mattresses because the floor matting is stuffed and springy. And a room is not permanent in its size: the screens separating one room from another can be removed, making possibly three closed rooms into one airy one, as is often done in summer.

2

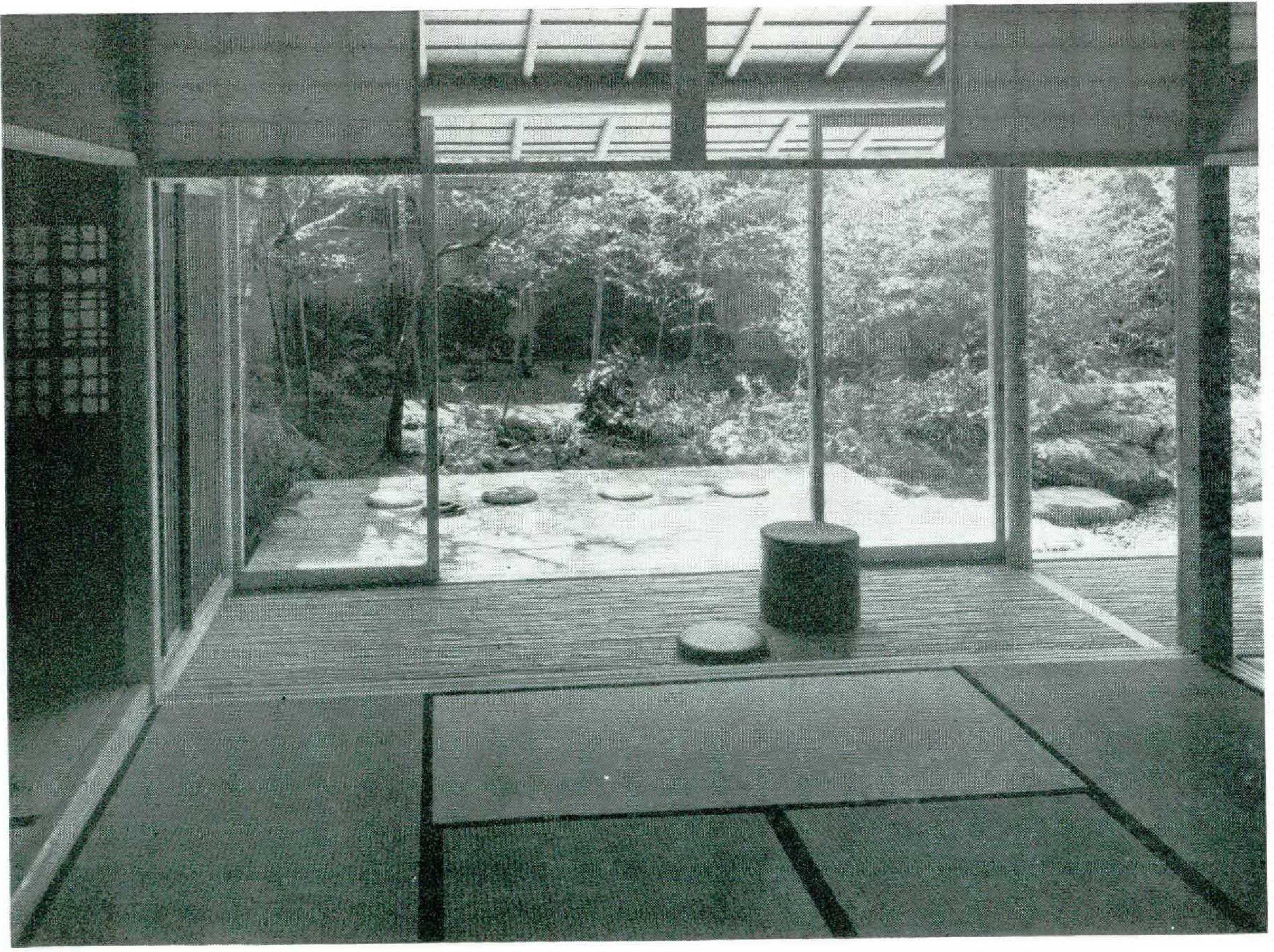

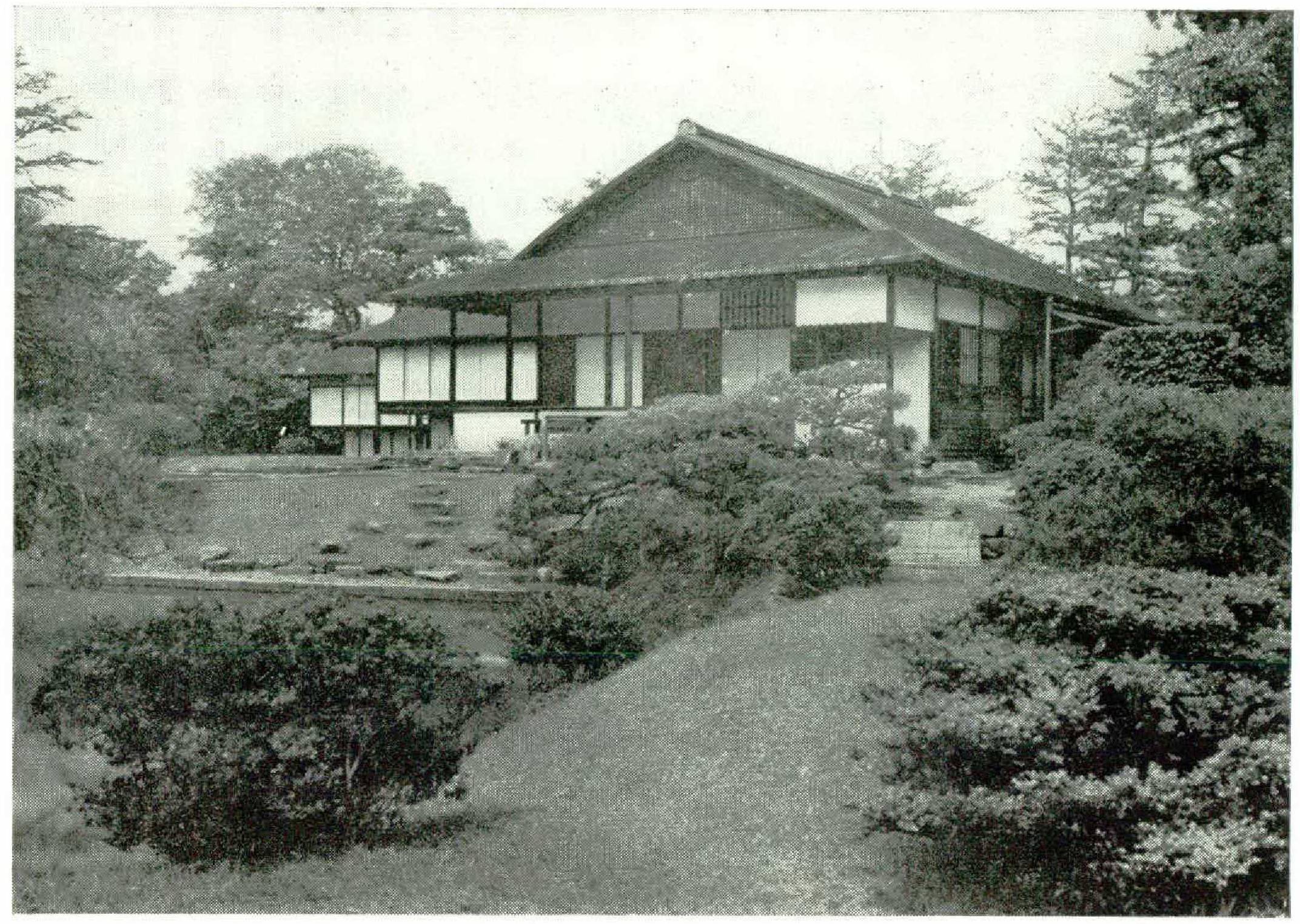

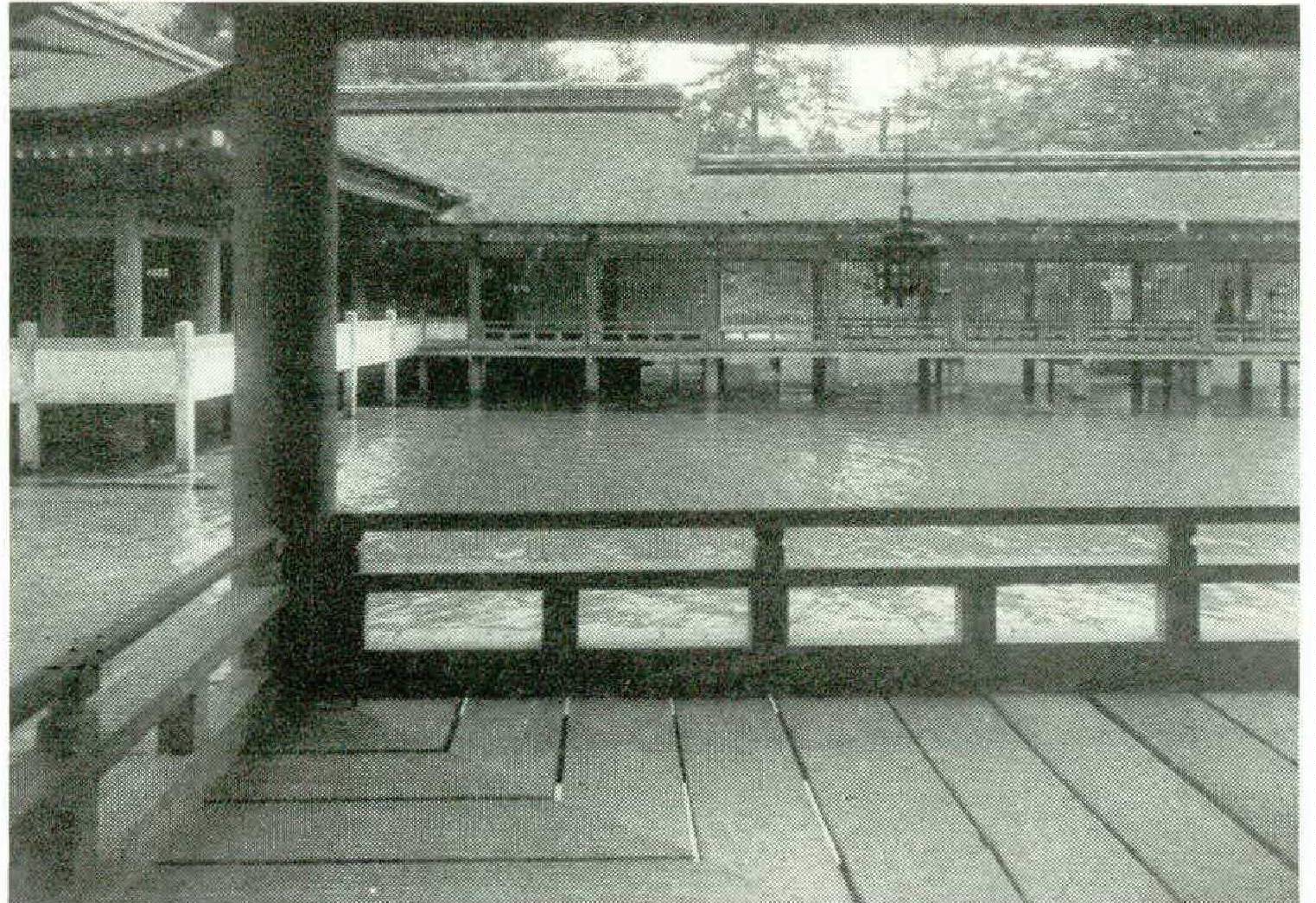

LET US now go back into the past of Japan’s architectural history and visit the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto (Plates 3 and 4). This building was erected over three hundred years ago for Prince Tomohito, a grandson of the Emperor Ogimachi (reigned 1557-1586, and completed by Tomohito’s son Tomotada. Its gardens cover almost sixteen acres. It is generally accepted as one of Japan’s architectural masterpieces. The present building, though modest in size compared to Western palaces, represents a great expansion of the original structure. The first architect for Katsura may have been Enshu Kobori, but in those days there were no architects in the modern sense, and it is more likely that Prince Tomohito himself, famed for his poetic tastes, designed the palace and gardens with the assistance of carpenters and gardeners, guided probably by his Tea Master, for the Tea Masters were then arbitri elegantiarum concerning aar more than the Tea Ceremony itself, and were connoisseurs of materials, their colors and textures.

Carpenters of that period also had higher skills; their pride in being able to assemble entire houses by the cut-joint method, without using a single nail, made them more like cabinetmakers on an architectural scale; and, with their guilds, they were the repositories of classic architectural tradition. Even today, the perfect finish of their work justifies continuance of the Japanese practice of leaving all structural components of a building exposed.

The skeleton of posts and beams is surmounted by wooden-shingled roofs. The sides are of sliding doors of wood and translucent paper (glass was not yet in use), protected by outer sliding wooden shutters. Katsura Villa visibly lacks decorations: its architectural beauty lies rather in the pleasing proportion of the walled and open segments, and the mutual spatial relationships among the bamboofloored moon-viewing balcony jutting from the front wing, the veranda under the eaves, and the sliding-door-enclosed rooms. Here the traditional Japanese mood is strikingly close to the aims of modern architectural design. The transom openings reaching the ceiling and the flush sliding board shutters, for example, surprise us pleasantly with their modernity.

Plate 4 shows this Villa’s garden. It is a microcosmic landscape composed of natural elements: sky, sunlight, trees, grass, water, rocks. Bridge, stepping stones, and the lantern at the pebbled peninsula’s tip tell that the garden is for human use. The pond, its water drawn from the nearby River Katsura, is, as always in Japanese gardens, an important feature. And the lantern has a good functional purpose: its reflection on the pond at night is beautiful. The rock formations here represent a style imported long ago from China, its underlying aesthetic principle being the naturalness of its beauty. Here again we note the affinity between Japanese love of natural forms and textures and the contemporary appreciation of abstract shapes and objects. All of Katsura’s stonework, and especially the stepping stones, are among the most elaborate in Japan, and are regarded as fine abstract design.

3

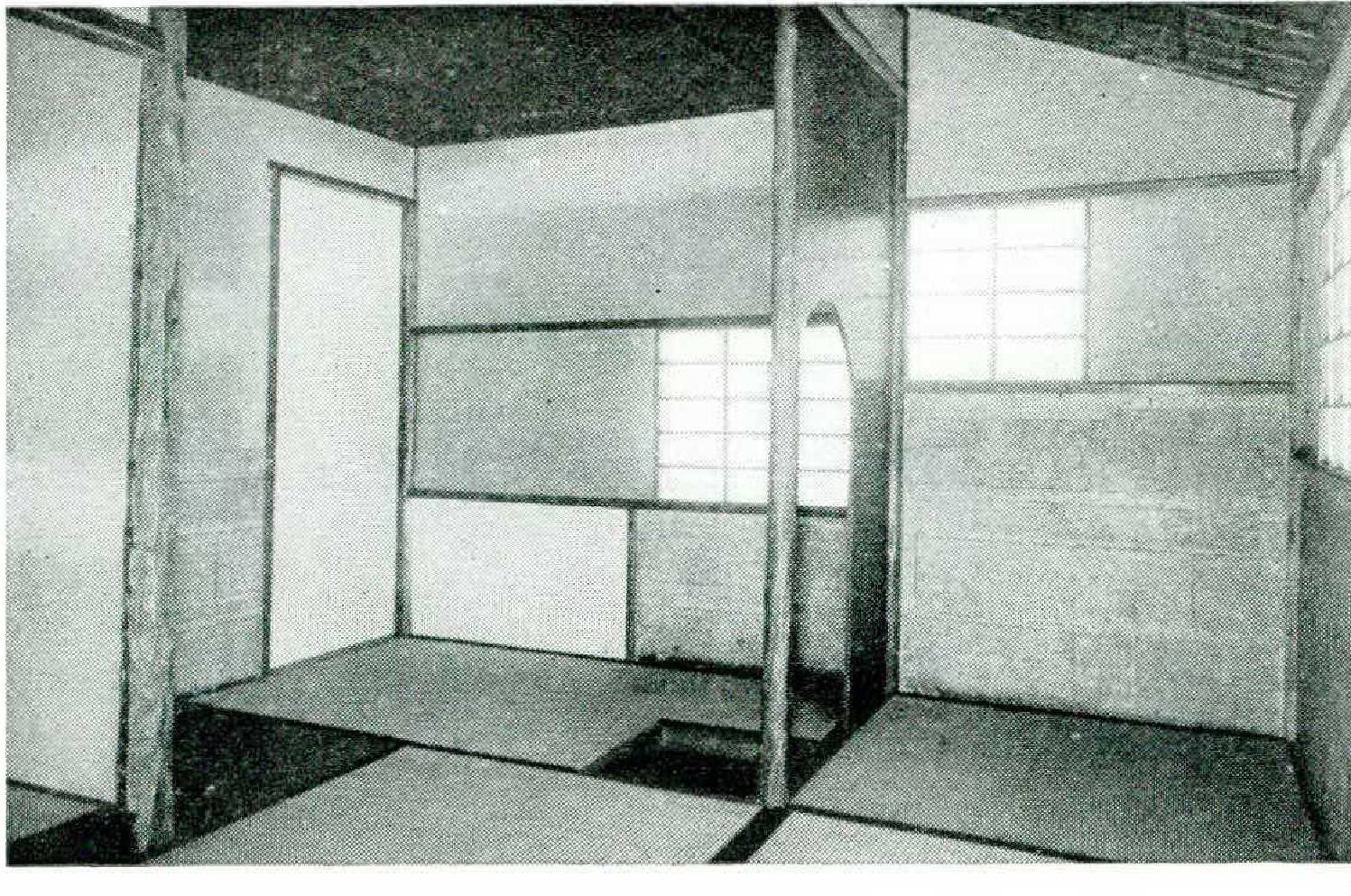

NOW let us visit a tea-house, that most characteristically Japanese phenomenon. Our example, in Plate 5, has the name of Jo-an. Built near Kyoto some four hundred years ago, it has been moved to its present location in Oiso near Tokyo. Its asymmetry was deliberate, for the Japanese believe that symmetry stunts the imagination.

A tea-room, generally entered by a “crawling-in door,” to suggest leaving pride outside, is usually nine feet by nine, and sometimes even smaller. Three to four guests are usual. It is necessary, therefore, that one’s movements be regulated by fixed rules so that the ceremony may proceed without awkwardness or embarrassing accidents. These rules determine where the host sits, where the water jar is placed, and where each guest, after bowing to the flower arrangement or picture in the tokonoma, takes his place. In this sense the tea-room is a diminufive laboratory of architectural functionalism. Its smallness is deliberate, with consideration not only for artistic effects but also for the psychological distance between host and guests. The tea-house is intentionally made of modest materials, to suggest impoverished refinement, but made with such workmanship as to be really very costly to build. Unlike the main house’s open structure, the usual tea-house is mostly walls; its windows, paper-covered, afford no outdoor view: this prevents one’s attention from being distracted. In the matted floor is cut out a square hearth, where, in winter, the kettle is heated on charcoal. The host sits beyond the hearth, his place set off by a central post, the nakabashira, which, symbolically, is gnarled or roughhewn.

The Tea Ceremony is a consciously aesthetic refashioning of daily routine into something beautiful removed from the everyday hustle and bustle. In one sense its pleasure is not so essentially different from children’s “playing house.” Yet it is a serious ceremony which has undergone centuries of refining. Its object is to concentrate one’s mind on beauty: while sipping tea or taking a simple meal, to chat with one’s friends and comment on the hanging scroll and the flowers arranged in a vase in the tokonoma niche, to appreciate the host’s impeccable tea-ware and other artistic implements used in the ceremony, and above all to savor the exquisite quiet of the little house and garden. It is a sanctuary from daily vexations, and right in the midst of a dusty hurrying city, one rediscovers here serenity and the sense of beauty. The tea-room and its ceremony contain lessons which profoundly influence Japanese life.

Because of its openness and the use merely of paper in the sliding doors which form most of the walls, the traditional Japanese house is delightful in summer, hut unquestionably cold in winter. To keep themselves warm in very cold weather the Japanese sit under a kotatsu, a wooden frame approximately two feet by two, which is fitted to the sunken hearth and covered with a quilt about six feet by six. In old Japan there was no heating system for the house itself. If this seems severe, we must remember two things: Japanese architectural functionalism resulted from a desire, chiefly ethical, to use minimum space to maximum advantage, with no thought of bodily comfort. And there existed also the ascetic influences of Buddhism, which taught liberation of the spirit through physical torment, and of Bushido (“The Way of the Warrior”), the moral code of chivalry of feudal times, which emphasized vigorous discipline and frugality, as well as loyalty and personal honor.

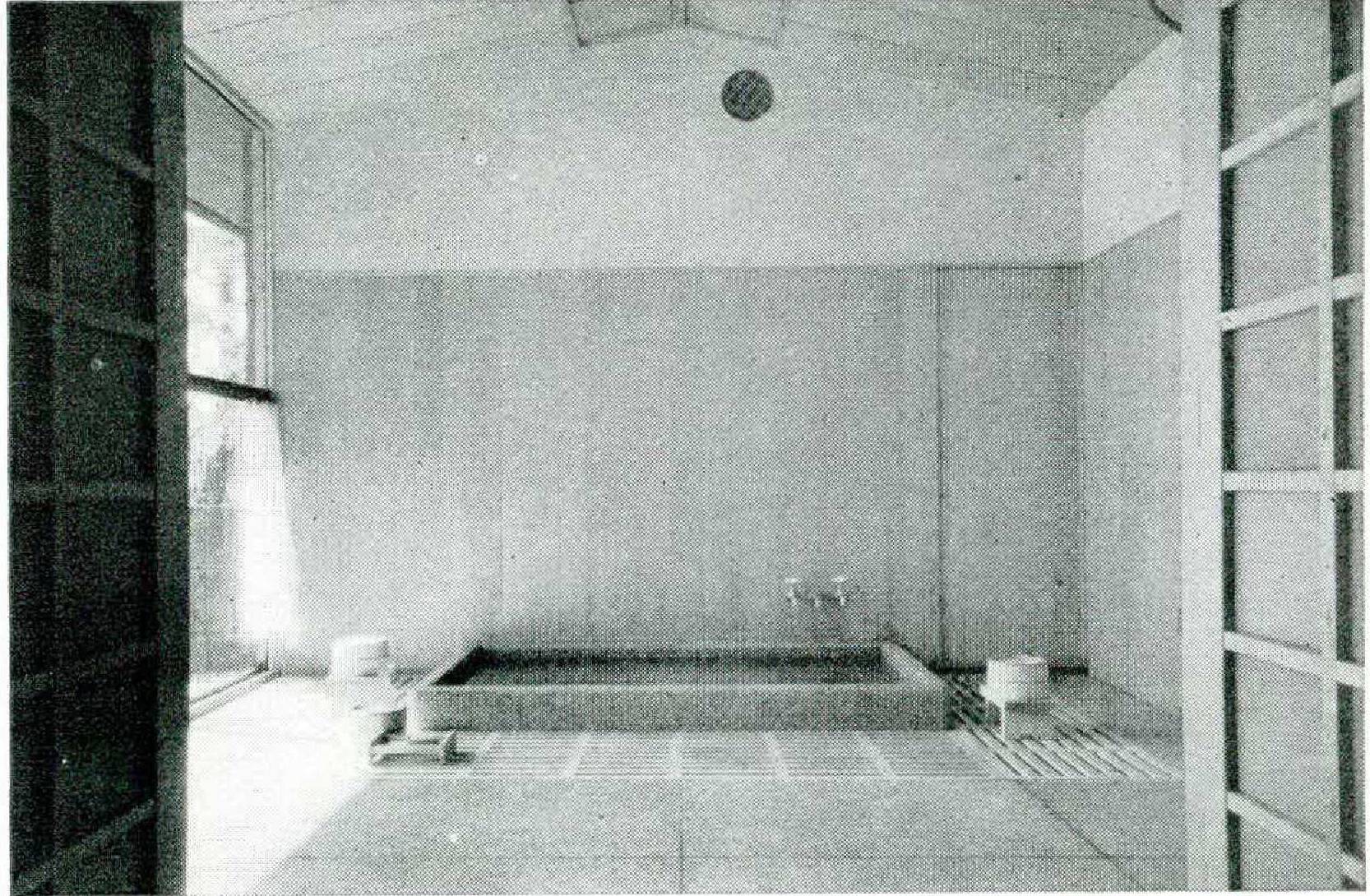

But it our heating systems are somewhat rudimentary, our arrangements for bathing are highly developed. Plate shows a bath in Hasshokan, the Japanese-style inn designed by Sutemi Horiguchi. This bathtub is granite, but baths in ordinary houses are usually of water-resisting Japanese cypress wood. Wood is preferred because it retains heat and repels the grime which attaches easily to stone or tile baths at the water level where the temperature changes. Bathing is a much-cherished daily practice in Japan, especially in view of the summer’s high humidity. The Japanese bathe by first washing and rinsing themselves outside the tub, standing on a drain board, then sitting in the tub for a relaxing soak in water heated to about 108° F.

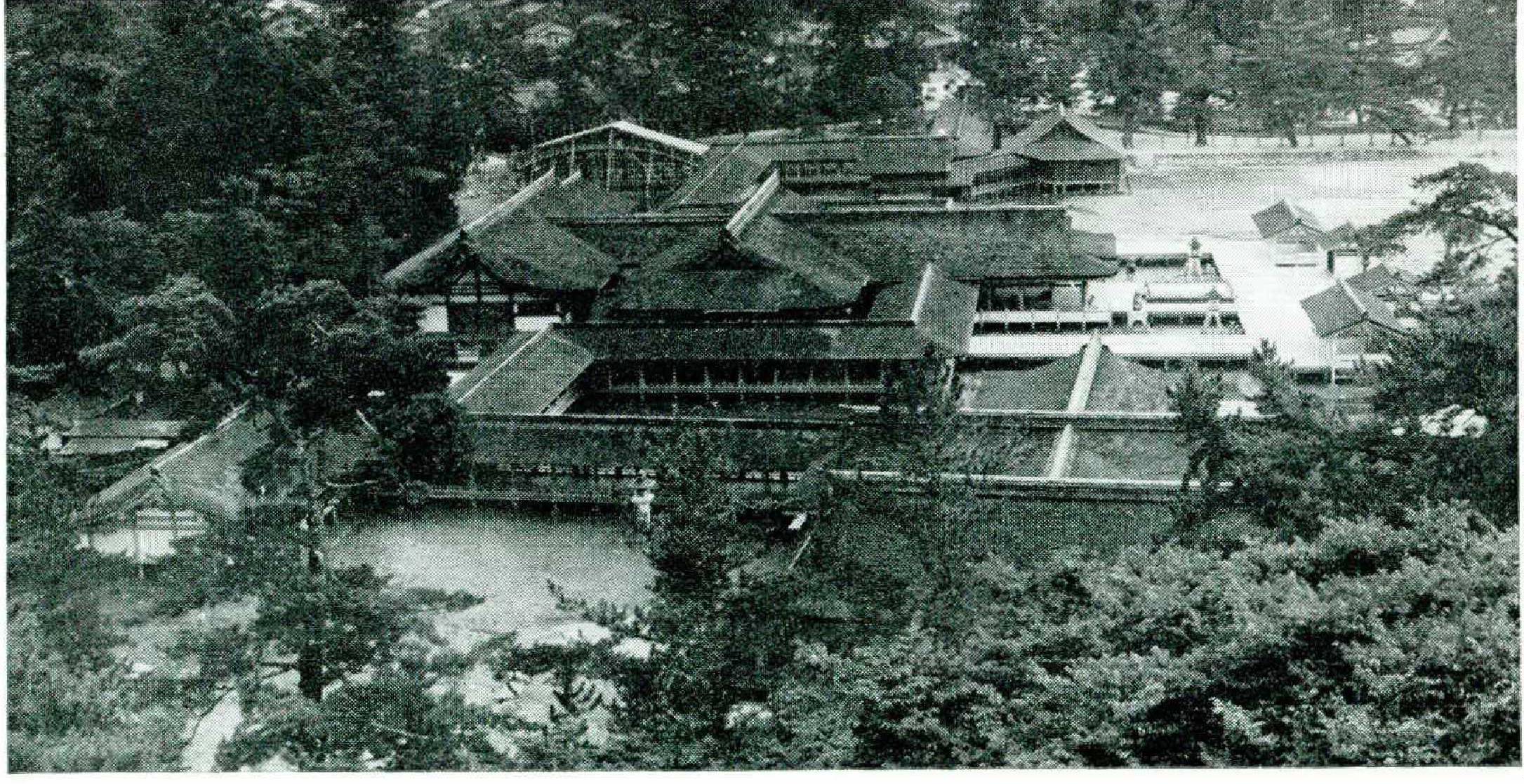

Let us now look at some examples of nonresidential architecture. Plates 7 and 8 show the Itsukushima Shinto Shrine, the sole notable instance in Japan of an important building jutting out over sea water — an inlet on an island in the Inland Sea. One is reminded of the prehistoric dwellings built over lakes in Switzerland. The Shrine may also be distantly related to South Sea Islanders’ houses built out over the water. It was reconstructed about five hundred years ago according to a style dating much further back. We modern architects cannot but marvel at the daring originality of t he design. The sepia-colored shingles, vermilion pillars, green doors, and white walls, all against a verdant landscape, make it a beautifully colorful sight. Architecturally, il well deserves its ranking as one of “The Three Sights of Japan.”

Nowadays the Itsukushima Shrine is thought of more as a scenic spot than as a place of worship. For Shinto has no longer a great hold on the modern Japanese; and those sects of Shinto adhered to by the great military families, even less. On the stage of the shrine are held performances of Bugaku, a quaint and colorful sort of ceremonial dance introduced from China about a thousand years ago, which is pictured in Mr. Ando’s essay on theater.

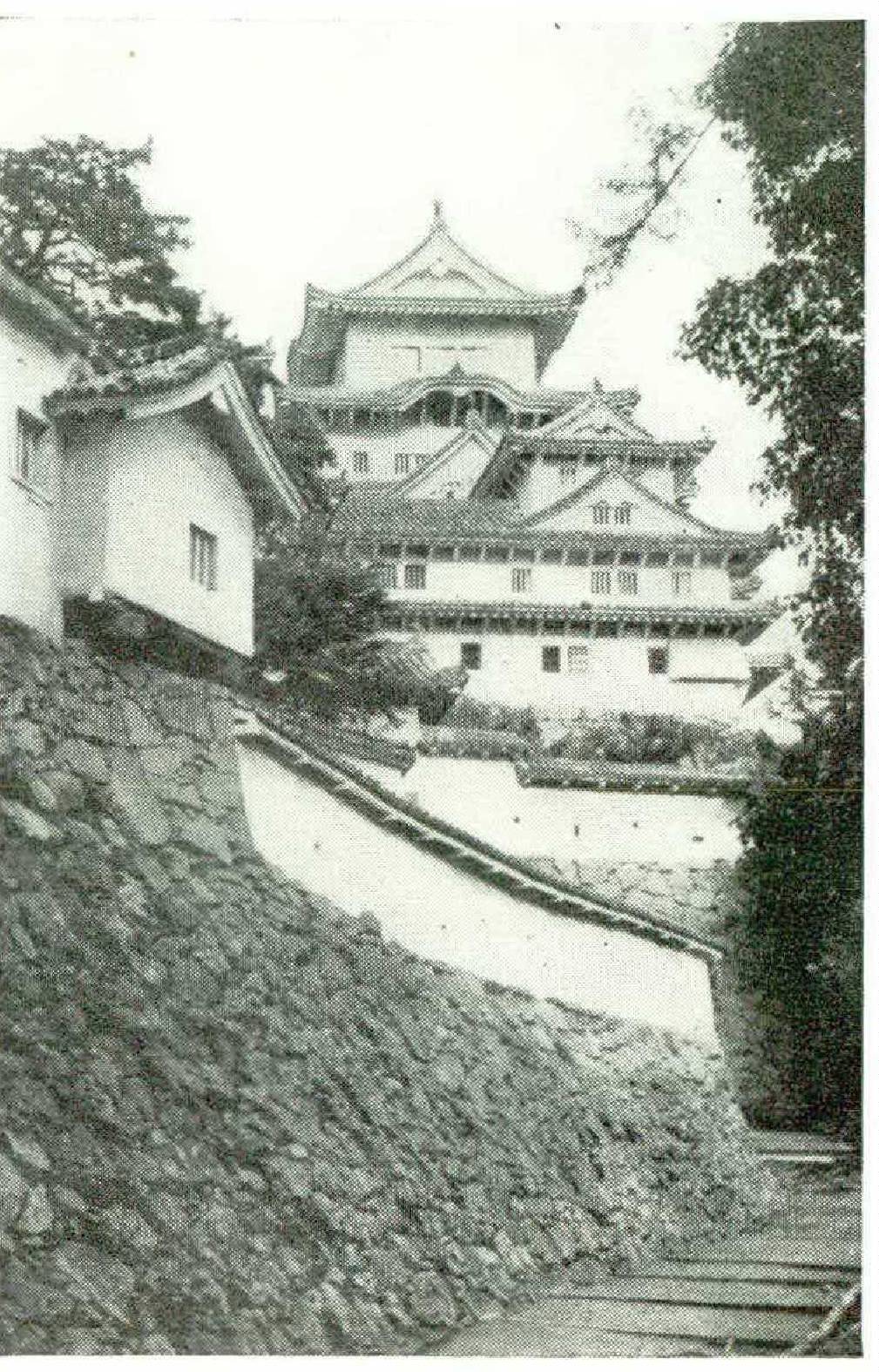

The Castle of Himeji (Plate 9) was begun in the fourteenth century and underwent later transformation. Like many other Japanese castles it was surrounded by a moat for protection. The photograph shows the donjon built upon a height. Its wooden fabric is covered with mud and plaster; its roofs are pantiled. Because of its white plaster, it is known also as “The White Heron Castle.” Japanese castles, products of civil wars among feudal lords, are said to show traces of Spanish castlebuilding; if so, this makes castles unique among our architectural monuments, which are otherwise overwhelmingly Chinese in style and type. As in medieval Europe, they were the armed centers around which villages clustered for protection. They are the architectural expression of the Daimyo’s and Samurai’s way of life. Himeji merits study, partly because it does not stop at dry militarism but reveals also a certain feeling for the lyric that even the feudal warriors of Bushido times must have had, and partly because buildings of such impressively large size are rare in Japan.

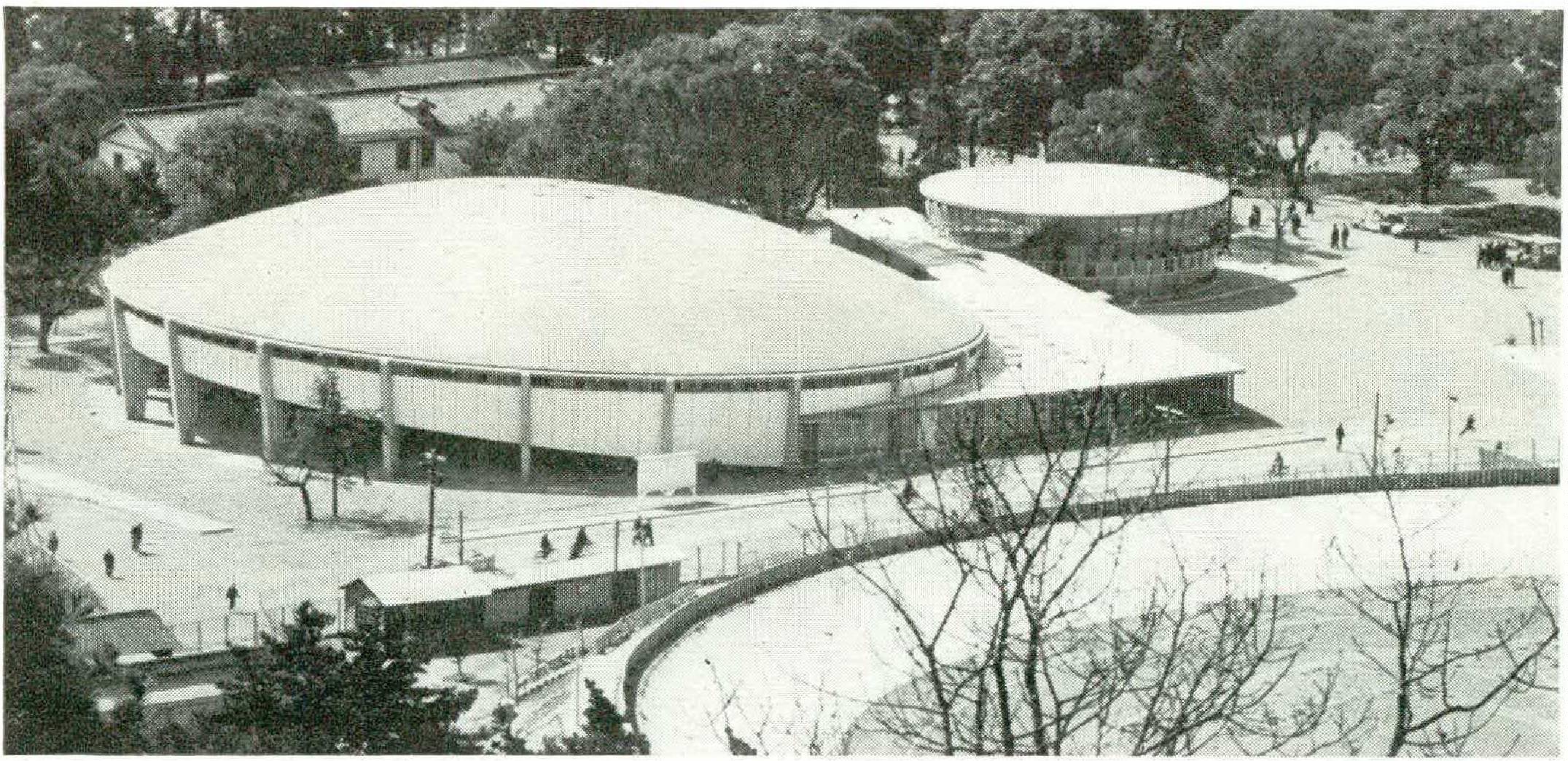

The last building to which I take you, in Plato 10, constitutes a great leap in time, from feudalism to ferro-concrete shell modern: architect Kenzo Tange’s 1953 gymnasium and Community Center in the provincial city of Matsuyama, Shikoku. But it is only an end product of Japan’s greatest transition, which dates from the Meiji Restoration a hundred years ago when Japan changed from a feudal state to a constitutional monarchy, and left its seclusion to become a nation whose doors were opened to the world. At this time public buildings began to be made not of wood, but of brick. Once the policy of Westernization had been adopted, the inevitable path of progress was from brick to reinforcedor ferro-concrete construction. The present Center is typical of Japan’s Westernized postwar architecture. If you visit Japan today you will find hundreds of modern-style structures, and parts of the central districts of great cities such as Tokyo and Osaka have much the same appearance as Berlin or Madrid, though we have not as yet built skyscrapers of soaring height.

You have now seen, in a few but very choice examples, what makes the traditions of Japanese architecture. Skeleton construction in which the roof rests, not on walls, but on post and lintel; sparseness of ornamentation; openness of rooms; unity of interior and garden; standardization and interchangeability of rush mats, and of sliding doors — all these, though materials and methods differ, are in line with the aims of modern architecture produced by steel-frame and ferro-concrete construction. This is why Japanese architecture is being studied by modern architects all over the world, and I feel that some of its best points have already been integrated in the West, particularly by such architects as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, and Mies van der Rohe. In point of openness and unify of house and garden, some recent California houses in the Bay Region are relatively pure examples of “Japanese" architecture.

Japanese architecture has above all the qualities of elasticity and adaptability. It often transcends time. The Ise Shrine, for example, which is the supreme monument of Japan, conveys the architecture of two thousand years ago, before the first contact with Chinese culture; yet this wooden structure is razed and re-created in exact replica on a different site every twenty years.

The question arises whether the art of living as crystallized in the Tea Ceremony has not something to contribute to Western culture. I think so, and venture to suggest it as worthy of consideration. The current does not, however, run only one way. The Japanese are now being overwhelmed by the inrush of Western civilization. They themselves are at a loss to tell, in the present chaos, which new ways of living will be found good. Ever since Commodore Perry came in 1853 and Japan turned toward the Western world, her people have confronted the problem of how to harmonize and integrate the two conflicting ways of life. And since World War II, there has been the huge problem of reconstruction under conditions of overpopulation and economic poverty. However, Japan’s situation is not unique. For, with the enormously increased contact and communication between peoples, cultures have never before influenced one another so deeply, and the particular problems of nations are becoming more and more dominated by one problem — the integration of the old and the new. It is a problem which must cast its reflection on architecture, too.

Translated by Masaki Kawaguchi