Scientists have studied a famous optical illusion to gain an understanding of how our brains process reality.

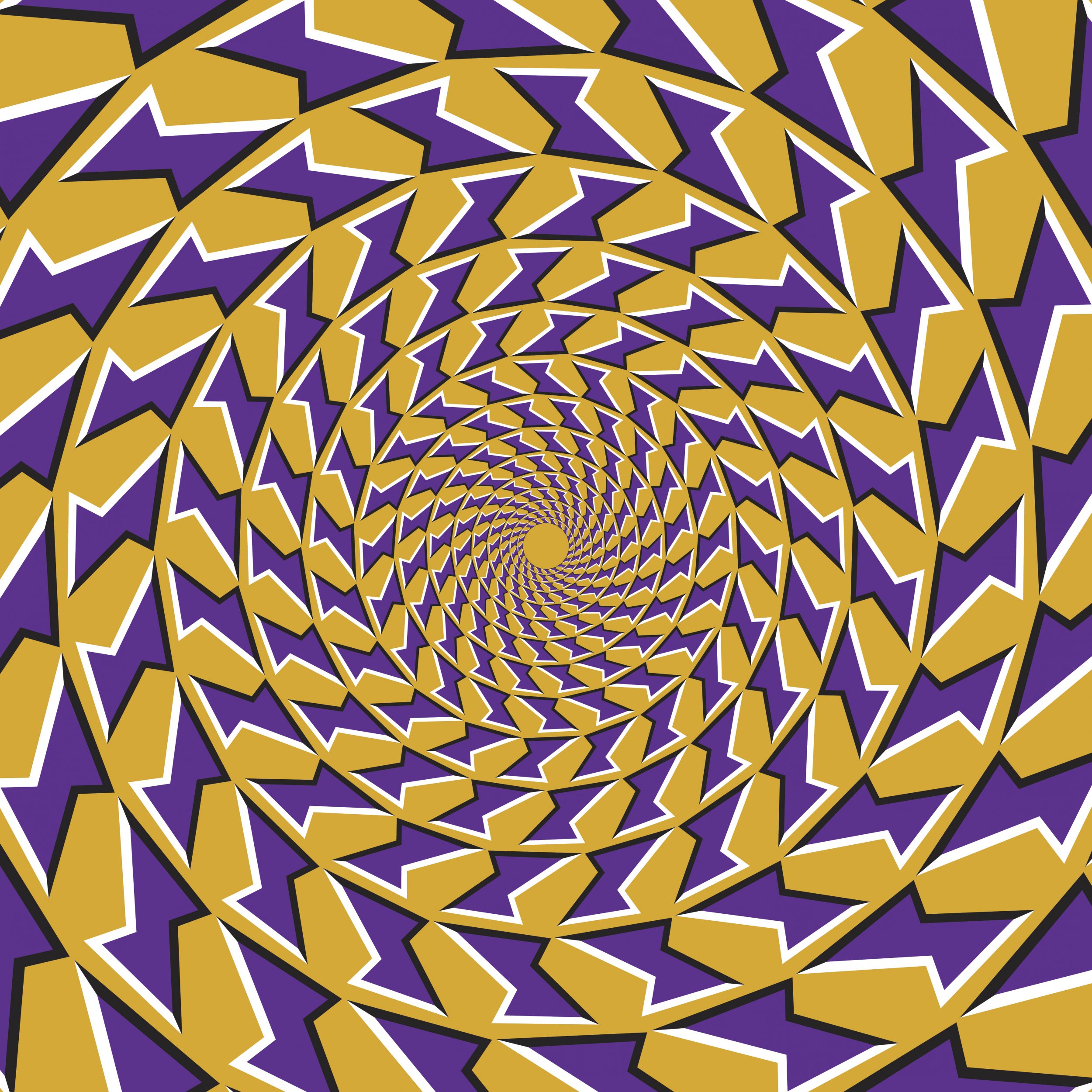

The research published in the journal JNeurosci centered around the Pinna-Brelstaff motion illusion: a series of thick lines arranged in concentric circles which appear to rotate when the viewer moves their head back and forth.

The scientists tested how parts of the brain that help us pick up on motion perception combine both real and illusory visual information to create the impression the image is moving. This enabled them to find cells that appear to process the illusion similarly to a moving object. And monkeys also appear to experience the illusion in this way.

For the study, nine human subjects (seven male and two female) aged between 22 to 30, were recruited. They were presented with a series of Pinna-Brelstaff motion illusions. Two rhesus monkey, who were trained to spot the difference between a version of the Pinna-Brelstaff illusion that didn't move and those that appeared to move, were also tested. Previously, the researchers used fMRI brain imaging equipment to identify the part of the brain that makes the image appear as if it is rotating.

This time, they found a processing gap of around 15 milliseconds by neurons in the medial superior temporal area, which are critical for picking up visual motion, helped to make the still image come to life.

Dr. Ian Max Andolina at the Institute of Neuroscience, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China, told Newsweek: "Navigating through the world requires our brain to be able to compute the direction in which we are heading; this is critical for day-to-day life. To do this, motion information has to be combined from every point in the space around us and processed efficiently. But how this occurs is not very well understood.

"Our study utilised a celebrated illusion to study how this information is combined by the brain. The Pinna illusion carefully introduces local biases, and unlike other illusions these can be well controlled."

He continued: "We can now say that monkeys not only perceive illusions as we do, but with a similar subjective magnitude. As primates (human and macaque), we are filled with unconscious biases, and visual illusions are a particularly visceral example of this. We have shown in the best detail yet within the circuits and cells that build our brain, how parts of this process occurs."

In the future, they hope to pinpoint the part of the brain that produces the final perception, Andolina said.

However, that likely won't be in the near future, he said: "With current technologies we cannot yet solve this ultimate mystery, as it requires monitoring neural activity across the whole brain with very high spatial and temporal precision."

This is the latest study to investigate the differences between reality and how we perceive it. Last year, scientists found that imagining an object while you hear a sound can change how you go on to perceive that sound. The research into the ventriloquist illusion was publsihed in the journal Psychological Science.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kashmira Gander is Deputy Science Editor at Newsweek. Her interests include health, gender, LGBTQIA+ issues, human rights, subcultures, music, and lifestyle. Her ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.