lady jane

Jane Birkin on Her Regrets, Romances, and Renewed Sense of Self

Photo by Nathaniel Goldberg.

What’s it like being the most beautiful woman in the world? At 74 (as of yesterday), Jane Birkin is tired of answering that question. So we asked the storied British actor, musician, and icon of French New Wave fashion some other ones, lifted from Glenn O’Brien’s 1977 interview with Andy Warhol. Does Jane Birkin get drunk? Does Jane Birkin believe in god? What about marriage? (She had one, but she would’ve done it again.) Though it’s a far cry from her days of heavy panting with Serge Gainsbourg, Birkin’s latest album, Oh! Pardon, tu dormais—direct translation: “Oh! Sorry, you were sleeping”—is her most intimate one yet, a reconciliation with the grief of losing her late daughter, Kate Barry, and other lingering ghosts. Locked down in her Paris flat with her new bulldog puppy, Birkin answers wistfully about her regrets, her romances, and her renewed sense of self: “I realize how nice it is when people like what you write or what you paint or what you do.”

———

SARAH NECHAMKIN: When did you first produce something musical? That can be as loose of a translation as you’d like.

JANE BIRKIN: Well, I suppose “Je T’aime… Moi Non Plus” was the first thing I did musically. But that isn’t entirely correct because I did do a musical with John Barry [Birkin’s ex-husband] when I was 17 called Passion Flower Hotel, with songs like “I Must I Must I Must Increase My Bust.” I was the figure of fun in the musical and they used my flat chest and bandy legs as the fun image. I did have a little song, but it wasn’t until “Je T’aime… Moi Non Plus” that somebody thought I had a pretty voice.

NECHAMKIN: How old were you at the time?

BIRKIN: 20.

NECHAMKIN: And did you know you wanted to become a musician then, or it just happened?

BIRKIN: No, I didn’t want to be a musician, it just happened that I fell in love with Serge Gainsbourg. He’d made this song with Brigitte Bardot the year before, and he asked me if I wanted to sing it, and out of jealousy I said yes because I didn’t want anybody else to be singing it. It sounded to me as if they’d made it in a telephone cubicle. So I said, “Yes, yes, of course,” just out of loving him and being scared stiff that he would be with some beautiful blonde. I had no ambition as a singer. I lived with him, he wrote me songs. We came back to France with that song, and the head of Universal at the time said, “Look, kids, I’m ready to go to prison, but for a long playing record, so go back to England and do another 10 songs. We’ll bring it out under a cellophane cover, saying it’s not for minors.” So we went back to England and I did sing about another five songs just to plumb it out a bit. And after that Serge wrote me a song until his dying day, so I didn’t really have to think about whether I was a singer or not; I just sang his songs, which were amongst the most beautiful ever.

NECHAMKIN: So jealousy served you well.

BIRKIN: It served me very well. Instinctive jealousy.

NECHAMKIN: What did you do for fun when you were a teenager?

BIRKIN: The best fun was with my brother and sister on the beach in the Isle of White. My parents made a movie with us called “The Pirate,” and my father played the pirate and my sister and I both got kidnapped by him and then saved by my brother. And then my brother made a movie with me and his best friend, Simon Williams, and I was supposed to die of tuberculosis on a beach in Brighton. And there was a kissing scene in the Battersea Fun Fair Lake and he filmed it, and then he showed that film at his boarding school, and he wrote on it “censored” so people got a thrill, thinking they were going to see something really adventurous. That was really my first part. I got it because my brother was in love with Hayley Mills, and she was in Los Angeles making a film for Disney, so she couldn’t do it, and that’s why he asked me, as a second choice. I was only too pleased.

NECHAMKIN: Did you go to the movies as a kid?

BIRKIN: Yes, we did, to see Yul Brynner in The Ten Commandments and things like that. Nothing particularly adventurous. Actually, the films that mean a lot for me were probably the kitchen sink dramas I saw when I was a teenager—A Kind of Loving, The L-Shaped Room, and all those deeply erotic black-and-white English movies that were made in the ’60s. My parents took me because they were A movies. You had to go with an adult, and I remember sitting between my parents in the classic cinema, sort of sweating because I was watching something so frightfully erotic. It was a sort of awakening of feelings, I suppose—sexual feelings.

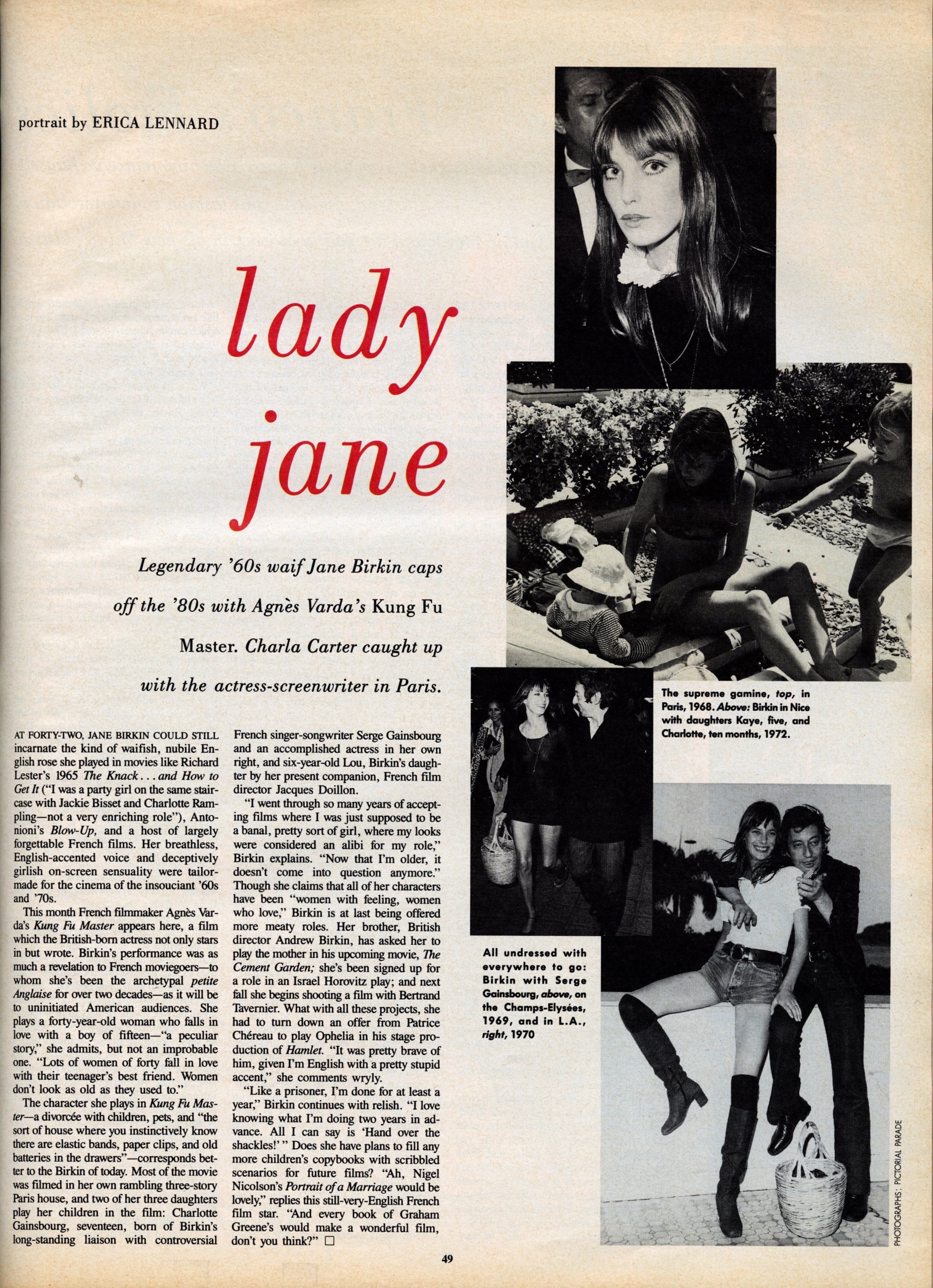

Birkin in the July 1989 issue of Interview. Portrait by Erica Lennard. Photos courtesy Pictorial Parade.

NECHAMKIN: Did you imagine that you would be an actress at the time?

BIRKIN: No way, because my mother was a theater actress of great beauty, and when people said to me, “Are you Judy Campbell’s daughter,” and I said, “Yes,” they said, “Oh, well you don’t really look like her. You don’t have the same…” and so I said, “The same class?” and they said, “Yes, that’s probably it.” So I thought, “Well, I’ve got no hope there.” I did ask Carol Reed, my father’s cousin who was making a film called The Agony and the Ecstasy in Rome with Rex Harrison and Charlton Heston, “Do you think I have a chance in the movies?” He said, “That really depends if the camera falls in love with you.”

On that advice, I went up for an audition when I was 17, for a Graham Greene play called Carving a Statue. I forgot all the text, and they said, “Oh, that doesn’t matter, you’re going to play a deaf and dumb girl.” So what good luck, I got my first part by making a fool of myself. I think my mother always thought that I hadn’t worked hard enough for it, that I didn’t go through Rafferty Company or go to drama school. But it was too late; I was pretty and I was sort of caught up in suddenly doing things. After Carving a Statue, I did Passion Flower Hotel with John Barry, got married to John Barry, and had my daughter, Kate. And then, when he left me and went to America, I left for France with my daughter and got a part in Slogan with Serge Gainsbourg, and fell in love with him. I didn’t really have time to think. I had no great ambition. Ambition came later.

NECHAMKIN: Did you encourage your daughter, or all of your children, to pursue that as well?

BIRKIN: Very much so, because I must’ve left Serge when Charlotte [Gainsbourg] was about twelve, and Jacques Doillon and I were looking for a kid to play in The Pirate. I could see that Charlotte was interested. And so, we went to a casting lady and had lunch with her, and we said we’re looking for a 12-year-old girl to play in The Pirate, and she said, “Well, I’m looking for a little boy to be in this movie with Catherine Deneuve about a divorce.” So I said, “Could this little boy be a girl and when she smiles you feel like crying?” And she said, “Yes.”

So I said, “Well, she’s at home. Look no further,” and I went back home and I left Charlotte a note on the kitchen table saying, “Look, they’re doing a screen test down the end of the road.” She took the piece of paper and never talked about it again. And she got the part. I always thought that it was safer to be an actress at 12 than to be a lonely teenager at 12 and try to get into nightclubs. Because while Charlotte was getting the French version of Oscars, Kate was a 14-year-old getting into nightclubs because of famous parents, and that was a far more dangerous route.

Thank goodness she went into fashion. As Charlotte was already such a success, I felt terrible for Kate because she was the one suddenly who’s got this younger sister, where everything was smiling for her. So the good luck was that she was able to pass exams and become a fashion designer. And then, my daughter, Lou [Doillon], I didn’t know what to do with. She was already leaving school at 14 and playing truant. And she turned into the most intellectual of all, but at that time it wasn’t very visible; she was just terribly funny and very cute. I just saw her smoking pot behind the house and things like that, and I thought, “Oh my god, how dreadful. What will happen?” And my good fortune was that when she was 15 she was offered a film where she had to give a blow job to the boys at school. She got the part and I said, “Go for it.” She had no naked scenes or anything like that; it was just a very impertinent part. And she got it, and then she went on to make movie after movie, and then be in fashion and have her photo taken, and I kept thinking, “Oh, she hasn’t found her thing yet.”

And then suddenly I hear her strumming her guitar when she was 29, and she already had a baby when she was 19, so there was this nine-year-old child by her side, and she was singing this song called “I See You.” And I thought, “My god, that’s great,” so I rang my producer Etienne Daho, who I’d just made the record with, and I said, “Lou’s got this really great song. I think you should listen to it.” And so, suddenly, at 30 years old she’s got a Victoires de la musique as the Best Female Singer, and she said, “I’ve been born again.” She too has become someone, and now my children are ready to become more famous than I am. They’re known for what they do rather than for what they are, or just for being a pretty face, so I’m well satisfied.

Birkin’s daughters, from left: Lou Doillon, photographed for Interview by Daemian Smith + Christine Saurez in 2016; Charlotte Gainsbourg photographed by Sebastian Kim for Interview in 2012.

NECHAMKIN: Did you feel like, at the time, that you were known for being a pretty face, or did you feel recognized for your work?

BIRKIN: I don’t think I used to think about it at all. I loved doing nude photographs with Serge because I’d have my legs pulled so often at boarding school being told I was half a boy and half a girl. I went through misery when I was at school. And then with a marriage that went quite as wrong as the one I had with John Barry … I mean, I was 17 and he was 13 years older with two children, so it was quite something to be left by him. I felt like a real disaster. And so, to have been picked up by Serge, he took me to the Louvre to show me paintings and said, “This is what you look like,” and that he’d drawn people like me at art school because that’s what he thought was beautiful. I had such fun with him for a good 10 years, and I was doing lots of comedies on my own, so I had no reason to worry about my image or what people thought of me. They just seemed to think that I was good fun. When I decided to sing for real at 40, I cut all my hair off and dressed up as a boy. I realized then that I was fed up with the rather sexy image that I’d played along with. Serge said, “Oh, you’re not going to cut all your hair off. You must make yourself look like a lion.” I said, “I’m not going to make myself look like a lion. I’m fed up with looking like a lion. I’m going to cut it all off and wear boy’s clothes.” He said, “You’re going to make no effort at all?” I said, “No effort at all. I just want them to hear your music and your words.” And it was a treat. It was lovely.

And then I did Jacques Rivette films, and plays, and life was more interesting. I realized how nice it was when people like what you do, rather than what you are. Someone came up to Lou at a bus stop and said, “Oh god, I just love what you write.” And then they looked at me and said, “And you’re as pretty as ever,” and I thought, “Oh, I wish they had complimented me on my work.” I was quite envious.

NECHAMKIN: This is one of the Andy Warhol questions: Do you ever get drunk?

BIRKIN: I used to be so drunk, I didn’t even know where I was in the morning. I’d be in nightclubs until 5 o’clock in the morning, and then somehow got home and then woke up at two o’clock in the afternoon, picked up the children from school, had a quite normal life until about 10 o’clock in the evening, then started again. That was my life. I never touched drugs because they frightened me too much. I didn’t like the idea of it whizzing up and down your veins and into your head, and not being able to get it out.

NECHAMKIN: Did you give up alcohol?

BIRKIN: I had to. When Jacques Doillon and I separated, I went off to Sarajevo and I met [the French writer] Olivier Rolin, and then after that I got quite serious with singing. I made myself have a sort of Jewish-Christian morality thing, thinking if I had any pleasure at all, then the show wouldn’t work. I didn’t drink or smoke a cigarette for about a week before I did the show, then it would be a month before the show. I had no noble reasons at all; it was only out of fear of the above. When I got leukemia, then of course everything stopped. It hasn’t been hard at all because the very idea of being sick, the very idea of it going to your head, makes me panic. I simply hate it. I mean, I’m frightened by it. So, to even imagine my youth, I don’t know. It was another time.

NECHAMKIN: Do you believe in marriage?

BIRKIN: It’s a romantic idea. Of course I do. I see old people wandering about holding each other’s arms, and I think, “Too late, too late.” If I met somebody tomorrow, we wouldn’t be hobbling anywhere because we’ve only got about another 10 years and we’re all dead, so I think I probably messed up that one. I nearly did it with Serge. I did it with John Barry, but I think that was because I was brought up to think that you should never sleep with anyone unless they ask you to marry them, so thankfully he popped the question, and that was somehow alright.

But when I met Serge and he wanted some wonderful marriage, it started great, then it started being an enormous publicity stunt, because I knew Serge loved the press. I somehow thought the whole thing was not really very romantic at all. And then I heard I had to have a blood test, and he got me all uptight about it, and so I stupidly didn’t get married. Serge said, “If you can’t spare a drop of blood for me, then I’m not worth anything to you.” I was worried that it would change something because I’d been so hurt the first time. But, in fact, I really regret not having married Serge. If there was anyone I should’ve married, it was certainly him.

NECHAMKIN: What do you look at first on a woman and man when you see them?

BIRKIN: Well, I suppose it’s always a bit corny to say I look at their husband or their wife, but it does tell quite a lot. I usually find myself looking at women more than men. I don’t see that many fascinating men around. I don’t know why. Perhaps I’m not looking right. But I’ve not been devastated for a very long time, whereas I’ve found devastating and fascinating women, even as they get much older. The way your face becomes like an elephant’s knee—there’s a sort of beauty in it. I suppose one has to think that way, otherwise it will all be too mortifying. But I find women that think and women that write—Joan Didion, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Glenda Jackson—I just find myself so much more drawn to these women. For me, there’s nothing more beautiful than a woman at 40. It’s the sort of age where I find that there’s a blossoming. It’s what they’ve left behind, it’s what’s coming up, it’s the fragility of adolescence into middle age. And it’s probably a sort of Stephen Fry romantic idea, but I do find them very compelling, so I suppose I look at women.

NECHAMKIN: Do you believe in god?

BIRKIN: No. I believe in people, though. And I believe that there was a good man, no doubt, called Jesus. I find his history very fascinating, and the idea of the mystery, or why do you suddenly fall on your knees when you’re so frightened for somebody, or when you’re praying? All these childhood reactions come back. I suppose what I really find complicated are religions, or what religion does to people. Nobody escapes the fanatics. I mean, look at those Buddhists that were in Burma with Rohingya. All fanatics.

NECHAMKIN: Do you still dance?

BIRKIN: I wish I did. There was something by Michael Jackson on the radio the other day and suddenly I found myself dancing. And I’ve got a new pup. She was so surprised. I thought, “That’s probably the best exercise we can do.” Instead of doing Pilates and everything, as we’re not allowed to go out, I think we might as well put on a lot of dance music and start hopping around the apartment. Oh, no. She’s peeing on the carpet.

NECHAMKIN: What’s her name?

BIRKIN: Bella. She’s a very small bulldog, about the size of my hand. She’s only two months old so she’s not allowed out anyway, but she hasn’t quite got it worked out about peeing on the carpet. Being confined is pretty sad, but if you’ve got a four-legged friend with you, it’s just so wonderful.

NECHAMKIN: I adopted a dog two months ago. They’re perfect.

BIRKIN: You’re never alone. And their faithfulness makes you cry.