Proun 19D (1920 or 1921), one of El Lissitzky’s best-known works, offers different frames of interpretations closely related to the historiographical record of where and how the work has been displayed since its inception. While Proun 19D has been traditionally understood within the sociocultural context of the emergent Soviet Union, this essay focuses on Katherine Dreier’s ownership of the work in relationship to the early twentieth-century American and European interest in the spiritual capacity of abstract painting. Dreier bequeathed the painting to MoMA upon her death, and Tomaszewski offers a history of its display in the museum in relation to its reception.

El Lissitzky’s Proun 19D from the collection of The Museum of Modern Art was made sometime between 1920 and 1921, just a few years after the Russian Revolution, and has been traditionally understood within the sociocultural context of the emergent Soviet Union. In the catalogue Painting and Sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art (2015), Proun 19D is reproduced immediately after Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918) and Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Spatial Construction no. 12 (c. 1920), suggesting it is inextricably linked to Russian Constructivism.1I understand the term “Russian Constructivism” primarily in relation to the work of artists commonly associated with two institutions that emerged in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917: the INKhUK (Institute of Artistic Culture), founded in Moscow in 1920, and UNOVIS (Champions of the New Art), and artists’ collective founded in Vitebsk in 1919 and led by Kazimir Malevich and Marc Chagall. Lissitzky was a member of UNOVIS until 1922. Though both organizations were directly affected by the tectonic sociopolitical shift resulting from the Russian Revolution and the cultural need to reconstruct Russian society in the years that followed, they approached the new visual culture of Russia differently. INKhUK was primarily concerned with examining the material properties of objects and the concept of “spatial construction,” while UNOVIS evidenced a stylistically diverse approach that originated within Malevich’s Suprematist theories. For the first comprehensive scholarly analysis of Russian Constructivism, see Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1983). For a more recent study of Constructivism, focusing primarily on Moscow artists and evaluating their political affiliations, see Maria Gough, The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). Further underscoring its revolutionary political dimension, the Museum’s gallery label from 2010 interprets the work’s “radical reconception of space and material” as “a metaphor for and visualization of the fundamental transformations in society that [Lissitzky] thought would result from the Russian Revolution.”2See https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79040?locale=en.

Notwithstanding the ubiquity of this interpretation, a closer look at the life of Proun 19D exposes the divergent interpretations that the work has accrued since its inception. Never shown in the USSR, the painting was first exhibited in 1922, in Erste russische Kunstausstellung (The First Russian Art Exhibition) in Berlin, an official display of modern Russian art intended to promote Soviet cultural production abroad. Organized at a time of political reconciliation between the USSR and Germany, following the lifting of the Soviet blockade in 1922, the exhibition took place only several months after El Lissitzky’s relocation to Berlin, a period in which the artist’s close collaboration with Western artists such as Theo van Doesburg and Kurt Schwitters flourished.3Victor Margolin, The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917–1946(Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 67. MoMA’s Proun 19D was subsequently purchased by Katherine Dreier (1877–1952), a prominent German-born American collector known for her commitment to promoting modern art through a distinctly spiritual lens that universalized the notion of “Constructivism” and imbued abstraction with a cosmic dimension.4Dickran Tashijan, “‘A Big Cosmic Force’: Katherine S. Dreier and the Russian/Soviet Avant-Garde,” in The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America, ed. Jennifer R. Gross (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006), 45–73. When Lissitzky’s work finally entered the MoMA collection in 1953 as part of Katherine Dreier’s bequest, its meaning shifted yet again, as it was fitted into Alfred H. Barr Jr.’s formalist display of Russian avant-garde work organized as part of MoMA’s XXVth Anniversary Exhibition: Paintings from the Museum Collections (1954–55).5See Alfred Barr, Cubism and Abstract Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1936).

This essay’s primary aim is to investigate the historiographical record of Proun 19Dand to examine the history of its reception in the United States. My analysis begins with assessing the work’s political dimension vis-à-vis the Russian Revolution of 1917 and then moves on to focus on Dreier’s ownership of the work in relationship to the early twentieth-century American and European interest in the spiritual capacity of abstract painting.6By “spiritualism,” I refer here specifically to the theosophical movement cofounded by Helena Blavatsky in the United States in 1875. Its articulation in modern art was championed by Katherine Dreier through her 1926–27 International Exhibition of Modern Art Assembled by Société Anonyme at the Brooklyn Museum. For more on Katherine Dreier’s efforts to promote modern art through a distinctly spiritual lens, see Ruth L. Bohan, The Société Anonyme’s Brooklyn Exhibition: Katherine Dreier and Modernism in America (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1982). I conclude with an analysis of the divergent theoretical frameworks within which the work was placed after its arrival at MoMA, an examination that also functions as a case study of American efforts to institutionalize Russian avant-garde art. By evaluating the various ways in which the non-mimetic nature of Proun 19D lent itself to a plurality of readings that go beyond its traditional Russian Constructivist pedigree, I also seek to illuminate the polysemic potential of abstraction more broadly.

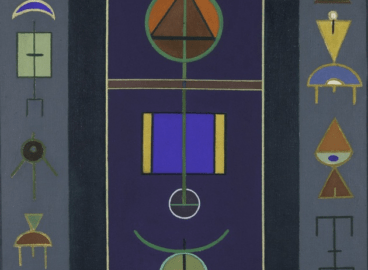

Lissitzky’s Prouns, which the artist began making sometime in 1919, infused the previously flat geometric forms of Suprematism with a sense of virtual architectural space.7The term “Proun” is understood as an acronym for “PROjekty Utverzhdeniya Novogo” or “Project for the Affirmation for the New.” See Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, ed., El Lissitzky: Life, Letters, Texts (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1980), 347; and Maria Gough, “The Language of Revolution” in Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art, ed. ed. Leah Dickerman (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 262–64. Instead of depicting two-dimensional planes of color, as Malevich did in his Suprematist compositions, Lissitzky employed axonometric projection. After drawing a geometric figure according to the rules of traditional Renaissance perspective, the artist would rotate the work ninety degrees and add a new volume corresponding to the new orientation. This shift effectively confounds the viewer’s relationship with the composition and contributes to what art historian Yve-Alain Bois describes as the Proun’s “radical reversibility.”8Yve-Alain Bois, “El Lissitzky: Radical Reversibility,” Art in America 76, no. 4 (April 1988): 160–81. Bois recognized the profound impact this visual effect has on the spectator and illustrated the specific political dimension of the work vis-à-vis the 1917 revolution. Accordingly, he asserts that the viewer “must be made continually to choose the coordinates of his or her visual field, which thereby become variable.”9Ibid. Thus, he acknowledges that the verticality of the painting was replaced by the horizontality of the document, providing in turn a “blueprint for the revolution.”10Ibid. Proun 19D meets the criteria for this kind of perspectival ambiguity: the top left-hand corner evidences an arrangement of polychromatic and interspersed geometric shapes that results in a multitude of viewpoints, confounding the spectator and destabilizing one’s spatial relationship to the picture plane. Further, a flat black line cuts across the composition diagonally, connecting the aforementioned assembly of shapes with a triangular dark form seen on the bottom. Finally, a gridlike structure, consisting of several rectangular and predominantly opaque shapes, grows out of the base shape, while a translucent yellow sphere is suspended above it.

While Malevich’s theories and teaching exerted a significant influence on Lissitzky, the political resonance of the Prouns is ambiguous. By 1922, UNOVIS, or Champions of New Art, an artists’ collective established in 1920 in the city Vitebsk, was split into two camps: one faction dedicated itself to socially engaged Productivism, while the other became loyal to a more distinctly philosophical interpretation of Suprematism.11See Aleksandra Semenovna Shatskikh, Vitebsk: The Life of Art (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007). Roughly at the same time, Lissitzky, who first participated in UNOVIS in 1920, departed Vitebsk for Berlin, providing much room for art historical debate regarding his ideological affiliations during this period. Some scholars have claimed that Lissitzky became an agent for the Soviet secret police; others have argued that his Communist views, even if implicit in the Prouns, were the result of little more than cultural conformism.12Scholarly positions on the political potential of Lissitzky’s Prouns, as well as Lissitzky’s ideological commitment to the Soviet Union, are divergent and ongoing. See, for example Margolin, The Struggle for Utopia; Bois, El Lissitzky; and Lodder, Russian Constructivism. Bois’s visually rigorous analysis of the revolutionary substructure in the Prouns situates them within the sociocultural milieu of the nascent Soviet Union and avoids the pitfalls of assigning a definitive political interpretation to these complex compositions. At the same time, however, it also sidesteps the important question of Lissitzky’s reception in the West. Though the artist later returned to the Soviet Union—associating himself with the propagandistic production of the early Stalinist period in the 1930s—his sojourn in Berlin in 1922 exposed him to an audience already familiar with diverse Western idioms of abstraction. Who was among the public that saw Lissitzky’s Proun 19D when it was first exhibited in 1922 and, more importantly, how much of a revolutionary dimension, as articulated by Bois, was this work capable of transmitting?13Unrelated to my argument directly is the influence of Lissitzky on contemporary German artists. See Meghan Forbes, “Magazines as Sites of Intersection: A New Look at the BAUHAUS and VKhUTEMAS,” September 26, 2018, post: Notes on Modern & Contemporary Art around the Globe, The Museum of Modern Art, https://post.at.moma.org/content_items/1179-magazines-as-sites-of-intersection-a-new-look-at-the-bauhaus-and-vkhutemas.

The First Great Russian Art Exhibition, which opened at van Diemen Gallery in Berlin on October 15, 1922, was an eclectic display—featuring approximately six hundred works representing styles that ranged from Russian Impressionism to the latest examples of Soviet Constructivism—that constituted an official cultural event between the USSR and Germany following the lifting of the Western blockade in January 1920 and the signing of the Treaty of Rapallo on April 16, 1922.14Otto Karl Werckmeister, “The ‘International’ of Modern Art: From Moscow to Berlin, 1918–1922,” in Künstlerischer Austausch: Artistic Exchange, vol. 3, ed. Thomas W. Gaehtgens (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1993), 553–71. The German left-wing journalist Arthur Hollitscher similarly expressed his enthusiasm for the revolution and its goals in the introduction: “It is no longer the prophetic vision of a single man that carries art forward; now it is the gigantic choice of the people’s triumphant spirit . . . Theory, born and fostered in the studio, . . . is now banished from the purified atmosphere of the victorious Revolution.” See Arthur Hollitscher, “Statement,” in The Tradition of Constructivism, ed. Stephen Bann, Documents of 20th-Century Art (New York: Viking Press, 1974), 74. While the van Diemen Gallery exhibition did not deliver a strong political message formally, scholars have recognized that its emphasis on Russian Constructivism—paired with the political undertone of its catalogue texts—provided an opportunity to win over the Western intellectual elite to the left.15Ibid. Lissitzky became closely associated with the exhibition as the designer of its catalogue’s cover. Adorned with letters that resemble factory gears that seem to morph into larger machine-like structures, Lissitzky’s composition exemplifies a type of utilitarian design commonly associated with Russian Constructivism. Otto Karl Werckmeister has pointed out that Lissitzky’s cover replaced an earlier attempt devoid of political emblems, a fact that made it difficult “to ignore the apparent ideological suggestions of this substitution,” an implicit nod to the Communist reorganization of post-revolutionary Russia.16Ibid., 563. The author also notes that Lissitzky did not play a key role in organizing the exhibition, despite being asked to design the cover.

Despite the show’s politicized goals, reviews of the First Great Russian Art Exhibition in Berlin reveal that critics might have, in fact, privileged artistic innovation over ideology in their reception of the show.17According to one critic, “In the place of the delicate colour harmonies of France or the mystical strivings of Germany, the Russians have revealed a stronger movement towards a greater plasticity and spatial force.” Cited in Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 231–33. In regards to Lissitzky’s oeuvre specifically, this tendency is further evident in art criticism that preceded the Berlin exhibition. In the July 1922 issue of the journal Das Kunstblatt, published only a few months before the show opened, the Hungarian critic and Bauhaus associate Ernst Kállai interprets Lissitzky’s Prouns as models “of technological qualities that mirrored aspects of the universe itself.” He wrote: “A technical planetary system keeps its balance, describes elliptical paths or sends elongated constructions with fixed wings out into the distance, aeroplanes of infinity. . . . The living, artistic kernel of the construction opens. What are mere utilitarian purposes beside this overflowing energy and dynamism?”18“Ernst Kállai: Lissitzky (1922),” in El Lissitzky, ed. Lissitzky-Küppers, 379. These “utilitarian” purposes in a traditional Russian Constructivist understanding imply a sustained study of materials and new spatial solutions put to use to aid in constructing the new Communist society. Yet, in the critic’s view, the primary purpose of Lissitzky’s work was, perhaps akin to Malevich’s Suprematism, to offer a new abstract idiom that did not rely on the outside world. As such, Kállai’s review indicates that Lissitzky’s disruption of the traditional relationship between the viewer and the picture plane—reinforced by the use of radical materials—may have been understood to have a predominantly cosmic dimension.19It seems relevant to mention the Russian cosmism movement, which embraced the spiritual potential of modern art in the years preceding the Russian Revolution. Boris Groys, ed. Russian Cosmism(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, February 2018).

Whether a similar interpretation of the work was embraced by Dreier, the future owner of Proun 19D and an avowed supporter of theosophy—a nondenominational spiritual movement advocating for unification of human beings and promoted in the United States by Helena Blavatsky—remains unknown.20See Bohan, The Société Anonyme’s Brooklyn Exhibition, 15–27. Nonetheless, tracing Dreier’s visit to the exhibition provides important clues regarding the collector’s approach to the Russian avant-garde, and to Lissitzky’s work in particular. Dreier visited Berlin in the fall of 1922 and hoped to diversify the predominantly French avant-garde aesthetic of the New York art circles, though she remained unaware of the van Diemen exhibition until she arrived in the city. Well acquainted with Russian modern art—she had, by then, organized exhibitions of works by Vasily Kandinsky and Aleksandr Archipenko in New York—Dreier nonetheless tended to see it, to quote Dickran Tashijan, through a “largely personalized lens” that was primarily reliant on aesthetic preoccupations and not dictated by her concern for the theoretical nuances between various Russian avant-garde movements.21Tashijan, “‘A Big Cosmic Force,’” 45–73. This approach was further evidenced by the stylistic and conceptual eclecticism of the works she acquired at the van Diemen exhibition.22In addition to Lissitzky’s Proun 19D, Dreier also bought Construction in Relief, made out of plastic and glass by Naum Gabo; a Suprematist oil painting by Alexander Davidovich Drewin, which is fittingly titled Suprematism; Kasmir Medunetsky’s Spatial Construction, which combines biomorphic abstract forms with geometric shapes; two versions of Lyubov Popova’s early Constructivist gouache paintings on wood panel, both titled Painterly Architectonic; At the Piano, an oil on canvas by Nadezhda Udaltsova; and Kazimir Malevich’s Cubo-Futurist composition titled Tochil’schik Printsip Mel’kaniia (The Knife Grinder or Principle of Glittering). When seen as a whole, they appear to share an important formal feature: prominent receding and projecting geometric planes, particularly evident in the recurring inclusion of a triangular shape. This characteristic is manifest in all of the paintings and sculptures selected by Dreier, for example in the oil painting titled Tochil’schik Printsip Mel’kaniia (The Knife Grinder or Principle of Glittering; 1912–13), Malevich painstakingly fragmented a human figure by fusing the Futurist interest in the machine with the Cubist geometries of pictorial space, and in Spatial Construction (Construction no. 557) from 1920, Konstantin Medunetsky undermined the visual stability of his abstract sculpture by piercing through it with an angled triangular plane.23See Erste Russische Kunst Austellung. Box 65, Folder 1705, Katherine S. Dreier Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University (after Dickran Tashijan). This specific formal characteristic is also alluded to in Dreier’s personal copy of the van Diemen catalogue, in which a paragraph containing statements that refer specifically to the “abstract planes” of Suprematism is marked.24Ibid. Perhaps in selecting these particular works, the collector was affirming the dematerialized and cosmic dimension of Suprematist theories promoted by Malevich, the progenitor of the movement.

Upon her return to New York, Dreier displayed Lissitzky’s Proun 19D at the 1924 exhibition Modern Russian Artists held in the Heckscher Building on Fifth Avenue at 57th Street. Intended to introduce Russian avant-garde art to the American public, the exhibition’s goal was hindered by shortcomings in Dreier’s holdings, prompting her to fill in the remaining gallery space with French modern paintings, including Cubist compositions by Georges Braque, Jean Metzinger, and Albert Gleizes. Art historian Barnaby Haran notes that the eclectic display resulted in a narrative stripped of its contemporary cultural context, especially in relation to the Soviet Union and Russian Constructivism.25Barnaby Haran, Watching the Red Dawn: The American Avant-Garde and the Soviet Union(Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 2016), 14. Works by Rodchenko and Vladimir Tatlin were shown next to paintings by Marc Chagall and David Burliuk, while examples of print media—a critical element in the development of the visual culture of the USSR—were missing entirely.26Ibid. Despite being accompanied by a relatively comprehensive catalogue, the show was marked by formal and art historical variety. Lissitzky’s Proun 19D, in particular, suffered from the surrounds. As a critic writing for the Christian Science Monitor misinterpreted, “This picture, which is aided and abetted by bits of old cardboard boxes and strips of silver paper, calls up the emotional contour of a frenzied golfer trapped in a bunker.”27Christian Science Monitor, March 10, 1924. See: Peter Nisbet, “El Lissitzky in the Proun Years: A Study of His Work and Thought, 1919–1927” (PhD diss., Yale University, 1995). Having likely recognized that Proun 19D evidenced a type of visual vocabulary that did not easily conform to predominant modernist tendencies originating from France, he read the work associatively, identifying it with a distinctly Western pastime.

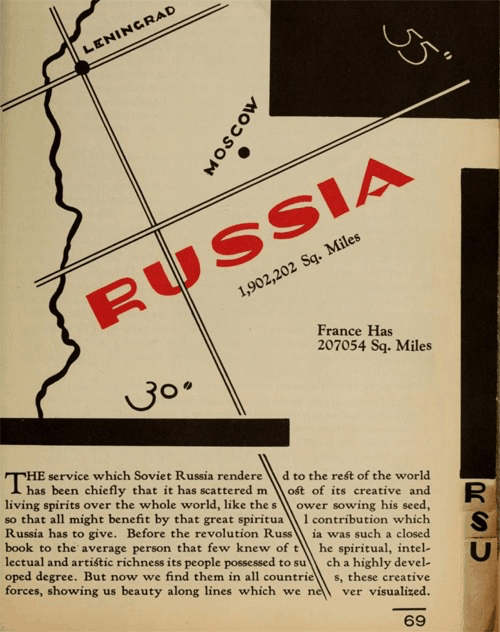

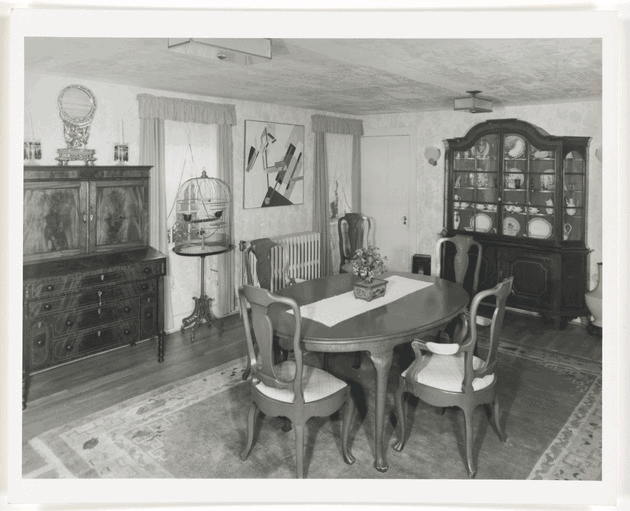

Dreier’s landmark exhibition of modern art at the Brooklyn Museum in 1926–27 offered the collector a chance to give Lissitzky’s work, as Tashijan has argued, “her own spiritual spin.”28Tashijan, “‘A Big Cosmic Force,’” 45–73. Illustrating “the close unity” that Dreier believed existed among all humans, the exhibition distributed diverse works by a range of artists freely throughout the galleries. Her entry note on Russia in the exhibition catalogue seems to frame the 1917 revolution primarily as an event that allowed the “spirituality” of Russian art to permeate other nations.29Katherine Dreier, “Russia,” Katherine S. Dreier, Modern Art. Catalogue of an International Exhibition of Modern Art Assembled by the Société Anonyme: Nov. 19, 1926 to Jan. 1, 1927(exh. cat. Brooklyn Museum), eds. Katherine S. Dreier and Constantin Aladjalov, New York 1926, n.p. Accordingly, the Prouns that Dreier chose to display in the Brooklyn Museum were intermingled with abstract works by Western artists, with Lissitzky’s l.n. 31 (c. 1922–24) turned upside down to fit her own vision. Though it is uncertain why Proun 19D was not included in the 1926–27 show, it is likely that Dreier had a particularly close connection to the work, since, for at least a decade, it hung in her house in Connecticut, which was commonly referred to as “The Haven.” In a 1941 photograph of Dreier’s residence, Lissitzky’s composition is shown tucked between two large windows and with a sizeable birdcage to its right in the small dining room. This placement is striking since, as Christine Poggi notes, Lisstizky was not in favor of his work being used to decorate bourgeois interiors.30Christine Poggi, “Circa 1922: Art, Technology, and the Activated Beholder,” in 1922: Literature, Culture, Politics, ed. Jean-Michel Rabaté (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 121. Although by 1941 Dreier had donated much of her collection to the Yale University Art Gallery, she did not part ways with Proun 19D until her death in 1952.

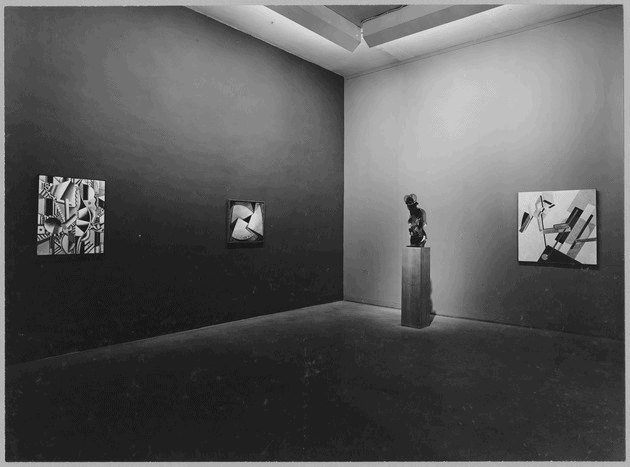

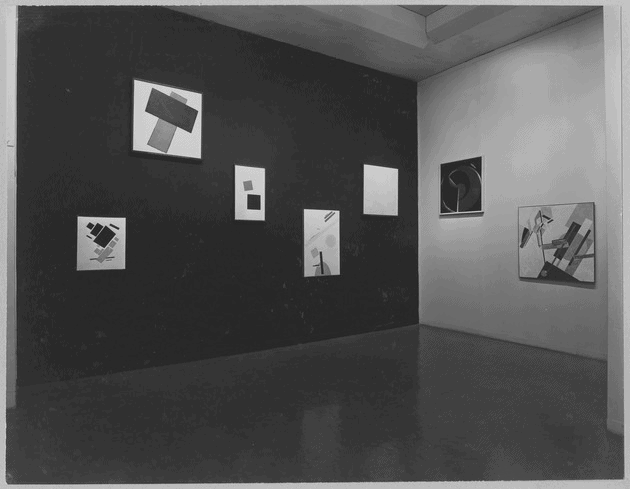

The composition subsequently became part of a larger bequest the collector made to MoMA before she died. The work was officially given to the Museum in 1953 and exhibited almost immediately in an ad-hoc summer installation organized by Alfred H. Barr Jr., then director of the collections. In one installation shot illustrating the stylistic and art historical diversity of Dreier’s collection, Proun 19D is seen placed next to three other works from Dreier’s bequest: a three-dimensional construction by Naum Gabo, a painting by Fernand Léger, and an abstract composition by American artist John Covert. In the following year, Lissitzky’s composition was swiftly separated from the rest of the bequest, having been refitted into a historical narrative of Russian avant-garde art in a display conceived by Barr.

If Dreier valued Lissitzky’s work for its ability to reflect the spiritual potential she believed formed a foundation of the modern era, then Barr employed Proun 19D to supplement his sequential model of modern art. Accordingly, Lissitzky’s work, having been swiftly separated from the rest of Dreier’s bequest in the XXVth Anniversary Exhibition, found itself in a space dedicated to Russian “nonobjective art” and thus with its Russian Constructivist lineage reinstated. The viewer would be expected to recognize the progression of modern Russian art: moving left to right, one would begin with Malevich’s earliest Suprematist compositions, made before 1917, then proceed to his post-revolutionary White on White, before finally encountering an example of Rodchenko’s Constructivist painting and Lissitzky’s Proun 19D, both of which were hung on the adjacent wall. Barr had a sustained interest in Lissitzky’s painterly practice and Prouns, but by the time of his landmark 1936 show Cubism and Abstract Art, the museum did not own any of these works. Dreier’s bequest of Proun 19D filled that lacuna, offering Barr a conclusion to the nonobjective experimentation of Suprematism in a painterly realm, augmented by daring experimentation in faktura.31For more on the Constructivist use of faktura and its significance, see Maria Gough, “Faktura: The Making of the Russian Avant-Garde,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 36 (Autumn 1999): 32–59. Understood within the context of the 1954–55 display, then, Proun 19D became a hermeneutic bridge, linking the flatness of the Russian avant-garde painting tradition to its later three-dimensional constructions, making it in turn a particularly well-suited object for Barr’s modernist teleology.

Moreover, the display of Lissitzky’s Proun 19D in the 1954–55 show seems to have served a purpose that was markedly political. Some twenty years earlier, Barr’s emphatic focus on the Russian avant-garde in Cubism and Abstract Art served to reinforce the freedom of expression in light of the rise of authoritarian regimes in Europe.32Leah Dickerman, “Abstraction in 1936: Cubism and Abstract Art at The Museum of Modern Art,” in Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art, ed. Leah Dickerman (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 364–76. During the inaugural event of the 1954–55 exhibition, that strategy—now targeting the postwar Soviet Union—was echoed in a speech titled “Freedom in the Arts,” delivered at MoMA by President Eisenhower. In it, the president fiercely reaffirmed the Cold War–era relevance of the First Amendment, while implicitly denouncing artistic oppression in the USSR. Participating directly in this cultural battle, MoMA’s collecting strategy in the 1950s, as has been recently illustrated, focused precisely on acquiring works that directly contradicted the doctrine of Soviet Socialist Realism, a style of artistic production traditionally understood in the West as totalitarian propaganda. Abstract painting was particularly suited for this purpose, as its repudiation of realistic representation implied independence and thus spoke directly to the cultural freedom the American government was hoping to preserve. Although Abstract Expressionism remained the most potent weapon against contemporary Soviet art—as Serge Guilbaut has shown—Barr’s selection of nonobjective Russian painting was a powerful gesture, pointing to the cultural relevance of the so-called reactionary style that had been prohibited in the Soviet Union since the early 1930s.33See Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983). A certain desire to demonstrate the oppressive plight of Russian abstract painters is also evident in MoMA’s publicity materials of the period. Confining Lissitzky’s prolific oeuvre to painterly practice, a 1953 press release describes the artist as someone who “was denied the freedom of his brush and died in disappointment probably about 1947.”34“Summer Exhibition of Recent Acquisitions and Works from the Museum Collection Offers a Wide Range of Interest,” June 24, 1953, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, https://www.moma.org/d/c/press_releases/W1siZiIsIjMyNTkwNCJdXQ.pdf?sha=8f957606f56912ee. Such rhetoric, which overlooked the artist’s cooperation with the Stalinist regime, likely prompted MoMA visitors to see Lissitzky as a victim of Communist oppression. The resolutely abstract nature of Proun 19D embodied the artistic creativity and freedom denied in the USSR. And, ironically, the intricately non-mimetic language of the composition now satisfied cultural expectations of the very ideology that the Russian Revolution was originally intending to combat.

One wonders how much the divergent frames of reference of Lissitzky’s composition relate to the uniquely American attempt to proselytize modern art in the first half of the twentieth century. Since the conclusion of Barr’s tenure, Proun 19D has been placed in diverse curatorial contexts, and oftentimes juxtaposed with contemporaneous Western works—yet Dreier’s role in bringing the painting to the United States and introducing it to the public has, until now, never been mentioned. In the most recent MoMA exhibition devoted to the history of the Russian avant-garde, A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde (2016–17), Lissitzky’s Proun 19D was hung next to another Proun painting, surrounded by other works from the series, and augmented by a comprehensive display of Lissitzky’s typographical and functional designs. Incorporating what Barnaby Haran noted was lacking in the 1924 exhibition, the MoMA display elucidated the historical context behind Lissitzky’s prolific oeuvre and made it possible for the viewer to draw visual parallels between the Prouns and other examples of his Constructivist practice. This thought-provoking choice was logical and warranted: seeing Proun 19D amid contemporaneous ephemera provided an important sociocultural contextualization. While the pristine quality of white museum walls stood in stark contrast to the domestic warmth of Dreier’s living room, neither the work’s provenance nor the history of its reception at MoMA were the organizing principles of the exhibition (one could hardly expect an expansive explanation of the painting’s ownership). And yet, one cannot help but wonder how much an examination of the work’s many lives would augment understanding of the object and its art historical significance. Perhaps then, resisting an urge to apply a stable signification to abstraction—and to modern art more broadly—can offer but one productive way to expand and reshape the canon.

The author would like to thank Elizabeth Buhe and David Joselit for their constructive feedback on this article.

- 1I understand the term “Russian Constructivism” primarily in relation to the work of artists commonly associated with two institutions that emerged in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917: the INKhUK (Institute of Artistic Culture), founded in Moscow in 1920, and UNOVIS (Champions of the New Art), and artists’ collective founded in Vitebsk in 1919 and led by Kazimir Malevich and Marc Chagall. Lissitzky was a member of UNOVIS until 1922. Though both organizations were directly affected by the tectonic sociopolitical shift resulting from the Russian Revolution and the cultural need to reconstruct Russian society in the years that followed, they approached the new visual culture of Russia differently. INKhUK was primarily concerned with examining the material properties of objects and the concept of “spatial construction,” while UNOVIS evidenced a stylistically diverse approach that originated within Malevich’s Suprematist theories. For the first comprehensive scholarly analysis of Russian Constructivism, see Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1983). For a more recent study of Constructivism, focusing primarily on Moscow artists and evaluating their political affiliations, see Maria Gough, The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

- 2

- 3Victor Margolin, The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917–1946(Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 67.

- 4Dickran Tashijan, “‘A Big Cosmic Force’: Katherine S. Dreier and the Russian/Soviet Avant-Garde,” in The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America, ed. Jennifer R. Gross (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006), 45–73.

- 5See Alfred Barr, Cubism and Abstract Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1936).

- 6By “spiritualism,” I refer here specifically to the theosophical movement cofounded by Helena Blavatsky in the United States in 1875. Its articulation in modern art was championed by Katherine Dreier through her 1926–27 International Exhibition of Modern Art Assembled by Société Anonyme at the Brooklyn Museum. For more on Katherine Dreier’s efforts to promote modern art through a distinctly spiritual lens, see Ruth L. Bohan, The Société Anonyme’s Brooklyn Exhibition: Katherine Dreier and Modernism in America (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1982).

- 7The term “Proun” is understood as an acronym for “PROjekty Utverzhdeniya Novogo” or “Project for the Affirmation for the New.” See Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, ed., El Lissitzky: Life, Letters, Texts (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1980), 347; and Maria Gough, “The Language of Revolution” in Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art, ed. ed. Leah Dickerman (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 262–64.

- 8Yve-Alain Bois, “El Lissitzky: Radical Reversibility,” Art in America 76, no. 4 (April 1988): 160–81.

- 9Ibid.

- 10Ibid.

- 11See Aleksandra Semenovna Shatskikh, Vitebsk: The Life of Art (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007).

- 12Scholarly positions on the political potential of Lissitzky’s Prouns, as well as Lissitzky’s ideological commitment to the Soviet Union, are divergent and ongoing. See, for example Margolin, The Struggle for Utopia; Bois, El Lissitzky; and Lodder, Russian Constructivism.

- 13Unrelated to my argument directly is the influence of Lissitzky on contemporary German artists. See Meghan Forbes, “Magazines as Sites of Intersection: A New Look at the BAUHAUS and VKhUTEMAS,” September 26, 2018, post: Notes on Modern & Contemporary Art around the Globe, The Museum of Modern Art, https://post.at.moma.org/content_items/1179-magazines-as-sites-of-intersection-a-new-look-at-the-bauhaus-and-vkhutemas.

- 14Otto Karl Werckmeister, “The ‘International’ of Modern Art: From Moscow to Berlin, 1918–1922,” in Künstlerischer Austausch: Artistic Exchange, vol. 3, ed. Thomas W. Gaehtgens (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1993), 553–71. The German left-wing journalist Arthur Hollitscher similarly expressed his enthusiasm for the revolution and its goals in the introduction: “It is no longer the prophetic vision of a single man that carries art forward; now it is the gigantic choice of the people’s triumphant spirit . . . Theory, born and fostered in the studio, . . . is now banished from the purified atmosphere of the victorious Revolution.” See Arthur Hollitscher, “Statement,” in The Tradition of Constructivism, ed. Stephen Bann, Documents of 20th-Century Art (New York: Viking Press, 1974), 74.

- 15Ibid.

- 16Ibid., 563. The author also notes that Lissitzky did not play a key role in organizing the exhibition, despite being asked to design the cover.

- 17According to one critic, “In the place of the delicate colour harmonies of France or the mystical strivings of Germany, the Russians have revealed a stronger movement towards a greater plasticity and spatial force.” Cited in Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 231–33.

- 18“Ernst Kállai: Lissitzky (1922),” in El Lissitzky, ed. Lissitzky-Küppers, 379.

- 19It seems relevant to mention the Russian cosmism movement, which embraced the spiritual potential of modern art in the years preceding the Russian Revolution. Boris Groys, ed. Russian Cosmism(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, February 2018).

- 20See Bohan, The Société Anonyme’s Brooklyn Exhibition, 15–27.

- 21Tashijan, “‘A Big Cosmic Force,’” 45–73.

- 22In addition to Lissitzky’s Proun 19D, Dreier also bought Construction in Relief, made out of plastic and glass by Naum Gabo; a Suprematist oil painting by Alexander Davidovich Drewin, which is fittingly titled Suprematism; Kasmir Medunetsky’s Spatial Construction, which combines biomorphic abstract forms with geometric shapes; two versions of Lyubov Popova’s early Constructivist gouache paintings on wood panel, both titled Painterly Architectonic; At the Piano, an oil on canvas by Nadezhda Udaltsova; and Kazimir Malevich’s Cubo-Futurist composition titled Tochil’schik Printsip Mel’kaniia (The Knife Grinder or Principle of Glittering).

- 23See Erste Russische Kunst Austellung. Box 65, Folder 1705, Katherine S. Dreier Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University (after Dickran Tashijan).

- 24Ibid.

- 25Barnaby Haran, Watching the Red Dawn: The American Avant-Garde and the Soviet Union(Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 2016), 14.

- 26Ibid.

- 27Christian Science Monitor, March 10, 1924. See: Peter Nisbet, “El Lissitzky in the Proun Years: A Study of His Work and Thought, 1919–1927” (PhD diss., Yale University, 1995).

- 28Tashijan, “‘A Big Cosmic Force,’” 45–73.

- 29Katherine Dreier, “Russia,” Katherine S. Dreier, Modern Art. Catalogue of an International Exhibition of Modern Art Assembled by the Société Anonyme: Nov. 19, 1926 to Jan. 1, 1927(exh. cat. Brooklyn Museum), eds. Katherine S. Dreier and Constantin Aladjalov, New York 1926, n.p.

- 30Christine Poggi, “Circa 1922: Art, Technology, and the Activated Beholder,” in 1922: Literature, Culture, Politics, ed. Jean-Michel Rabaté (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 121.

- 31For more on the Constructivist use of faktura and its significance, see Maria Gough, “Faktura: The Making of the Russian Avant-Garde,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 36 (Autumn 1999): 32–59.

- 32Leah Dickerman, “Abstraction in 1936: Cubism and Abstract Art at The Museum of Modern Art,” in Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art, ed. Leah Dickerman (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 364–76.

- 33See Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

- 34“Summer Exhibition of Recent Acquisitions and Works from the Museum Collection Offers a Wide Range of Interest,” June 24, 1953, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, https://www.moma.org/d/c/press_releases/W1siZiIsIjMyNTkwNCJdXQ.pdf?sha=8f957606f56912ee.