ArtSeen

Don McCullin

A retrospective at the Tate Britain

On View

Tate BritainFebruary 5– May 6, 2019

London

Few photographers have taken as many iconic photographs as Don McCullin (b. 1935). Think of the Vietnam War, and Shellshocked US Marine, The Battle of Hue (1968) will very likely pop up. Think of the Northern Ireland Conflict, and Northern Ireland, Londonderry (1971) will probably do the same. As to the lesser-known conflicts, in the case of Biafra, chances are a faded picture of Starving Twenty Four Year Old Mother with Child, Biafra (1968) will come to mind. McCullin has grown wary of the label "war photographer," and indeed the label is unfitting. His photographs have not only shaped collective memory; they have stood the test of time. It only makes sense that the Tate Britain would organize a retrospective, its first dedicated to a photographer, to celebrate his extraordinary career.

Showcasing over 250 images, developed by McCullin in his darkroom, the exhibition is roughly chronological, with photos grouped by locale. Interspersed with the iconic war images McCullin had shot on assignment for The Observer and The Sunday Times are pictures of the British poor, homeless, and disenfranchised that he took at home, as well as the landscape and still life photography that he turned to later in life when, haunted by memories, he sought an antidote to the horror he had seen as a correspondent.

The first cluster of images includes work McCullin produced in the course of three decades covering vicious civil wars and other Global South disasters, as well as his photographs of East Germany and Northern Ireland. It shows images of conflict in Cyprus, Congo, Biafra, Vietnam, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Lebanon, and Iraq, as well as the AIDS epidemic in Africa in the nineties. As such, at times it could begin feeling like an "atrocity exhibition," which, according to Susan Sontag, was the lot of "concerned" photojournalism at the end of the sixties. But right when you begin to feel numbed to insensitivity, McCullin gets under your skin with an image whose detached yet unrepentant humanism can't help but shock you back into conscience.

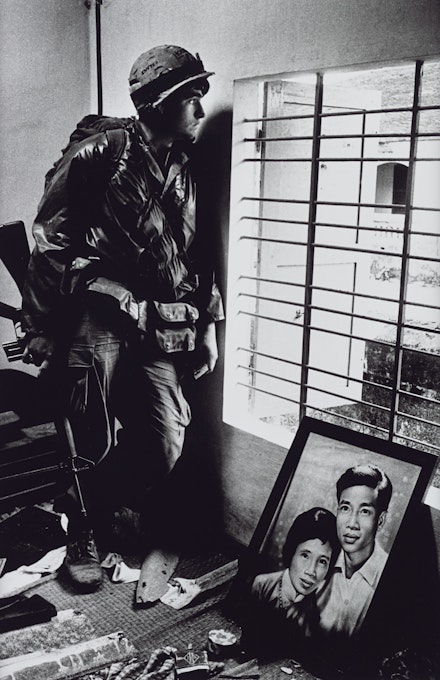

To me, it happened a few rooms in when I saw Turkish Woman Grieving for her Dead Husband (1964). The image portrays a gaunt, dark-haired woman, her face creased by grief, who is consoled by two older, head-scarved women and a crying child. It happened again, soon after, with A Young Dead North Vietnamese Soldier with his Possessions (1968), an image of a dead Viet Cong, the young soldier pictured with his treasured personal belongings. And it happened toward the end of the exhibition, with A Boy at the Funeral of his Father who Died of AIDS, Ndola, Kawama Cemetery, Zambia (2000), a frontal close-up of an African child's face, whose dignified expression is made all the more piercing by the dried marks of recent tears.

In a video which I found on the Tate website, the photojournalist walks the rooms of the retrospective and defines his work as "a silent protest against the futility of war." But McCullin's photographs do not actually depict the futility of war—images such as these show its unquantifiable wastefulness. They remind us, poignantly, that we are not dealing with statistics nor casualties, but actual human beings. McCullin's deeply empathetic gaze carries on in his documentary photographs, which often turn to be even more elegiac.

Among the pictures McCullin took of the homeless who lived in the East End in the seventies, there are some amazing portraits. But I prefer the ones McCullin took of the northern industrial landscapes and summertime Britain. McCullin came from a working-class background, and one could feel that these photos are not only social testimonies—concerned as they are with the British underclass—but also documents of an endangered way of life. Also, they show a unique eye for English quirks and a fair share of humor. My absolute favorites, in this respect were Consett, County Durham (1974), showing an English Teddy Boy posing with his girlfriend in the middle of some railroad tracks, with a smokestack as background; and Seaside Pier on the South Coast, Eastbourne, UK (1970), portraying four dozing sunbathers on lounging chairs.

No less striking are the meditative, quiet images of the English countryside, with its misty woods and marshes, which McCullin mostly shot in his beloved Somerset. Then there is his "Southern Frontiers" series, which documents ruins of buildings at the far ends of the Roman Empire—among them, Palmyra in Syria. As such, these landscapes are remnants of the Roman imperial drive, as well as of subsequent devastations. Equally filled with pathos, they are the most dramatic and grandiose photographs in the show, animated as they are by a fascination with historical monuments and the haunting awareness of the human toll their realization had taken.

The photographer's qualms about the impact of his own work notwithstanding, Don McCullin is a testament to photography's enduring power to affect. Some of these images may, as the photojournalist has said, "have had an insufficient role in ending the suffering of the people they depict." Still, almost 50years after being taken, they have lost none of their sharpness. Though insufficient propellers of direct political action, they still inspire that strange mix of sympathy and indignation that often works as its catalyst.