BRUNO MUNARI

AT THE BRERA

The others are us

The story of two brilliant minds that met at one of the key moments in the Pinacoteca’s history. Franco Russoli, the Process for the Museum, workshops for children, Bruno Munari and his work.

We must get people to understand that as long as art remains extraneous to the problems of life, it will only be of interest to a handful of people.

Bruno Munari

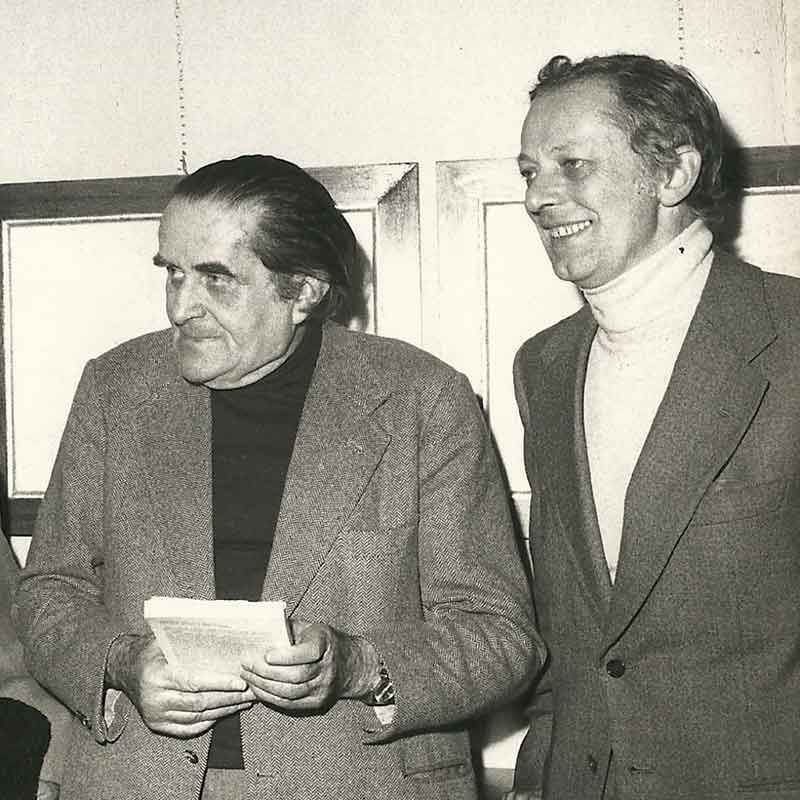

In 1956 Fernanda Wittgens, sensing that she was approaching the end of her life, made every effort to ensure that she would be succeeded by Franco Russoli, “a man aware of the need to merge the ethical and the intellectual”.

Russoli firmly believed that a museum’s educational mission lay in encouraging the public to become partners on an equal footing and to play an active role in the creation of culture. He saw the museum as a living workshop, as a “test bench” for critical thought and visual intelligence.

So, in his capacity as director in 1974, he decided to do something deliberately prevocational: with the support of all the staff, the Friends of Brera and the Milan museums, he temporarily closed the Pinacoteca “both on account of the appalling condition of the place as a whole and to highlight the impossibility of running the gallery properly owing to a shortage of funds, equipment, facilities and staff”.

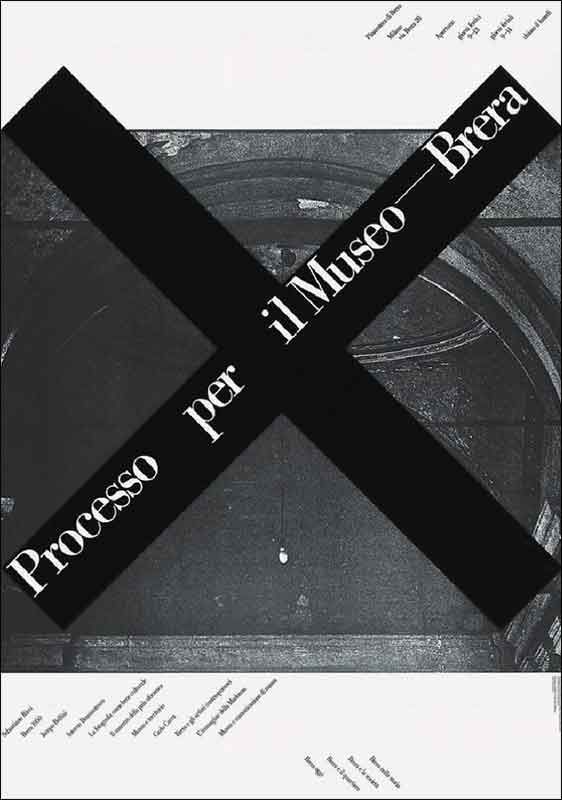

Several projects were implemented to improve the Brera complex’s condition in various areas, and two years later, in late 1976, he opened an exhibition entitled The Process for the Museum in the rooms of the Pinacoteca.

At the official opening, Russoli said:

People who work in museums now reject the ambiguous privilege of isolation […] of ‘pure’ experts who oversee the creation of tools without verifying their social usage. They refuse to act as the guardians of places designed for escapism or alienation, or as servants of the consumption of culture or of the political authorities. They demand that the right conditions be guaranteed […] for turning the museum into a venue in which the public ‘reappropriation’ over cultural heritage is guaranteed by management along social lines. […]

This approach to the concept of the museum must serve as the starting point for a strategy allowing us to create […] working tools for implementing the three different yet crucial functions of a museum: the best possible conservation and public display of cultural heritage; research work open to all those involved and interested; and treating works of art in such a way that the public feels it is participating in, and ‘contemporary’ with them, so that it can experience history as something relevant and problematic.”

An experimental exhibition which showcases the intellectual ‘processes’ triggered by the exhibitions in a museum, Brera, that is a ‘construction site’ for a debate involving artists, visitors and a range of different disciplines.

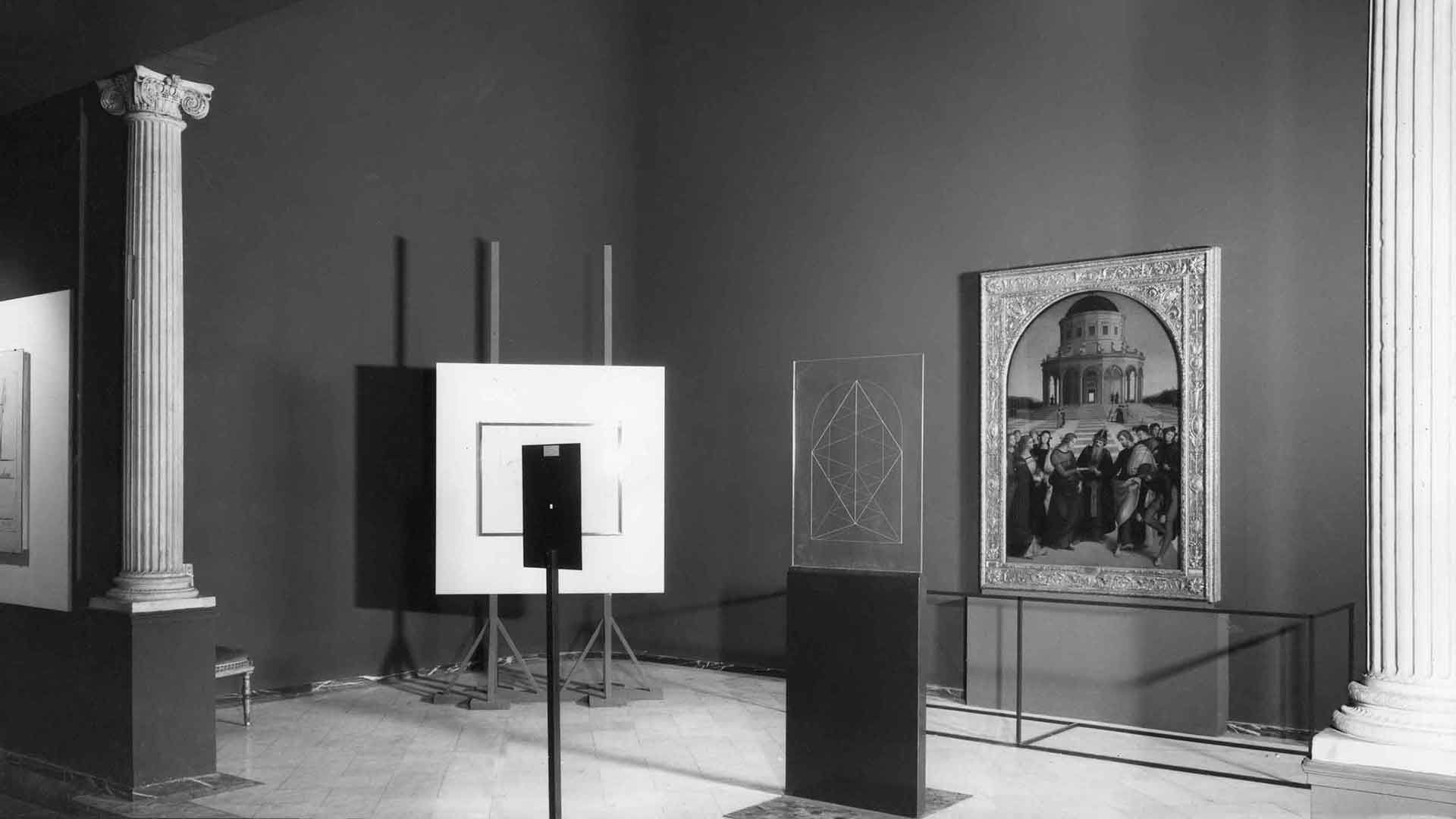

In the Process for the Museum, a deliberate attempt was made to break the bond between the architecture and the room as this was designed in the post-war time. One of the most emblematic instances of this was unquestionably the installation that Munari devised to encourage visitors to look differently at Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin on display in Room 24.

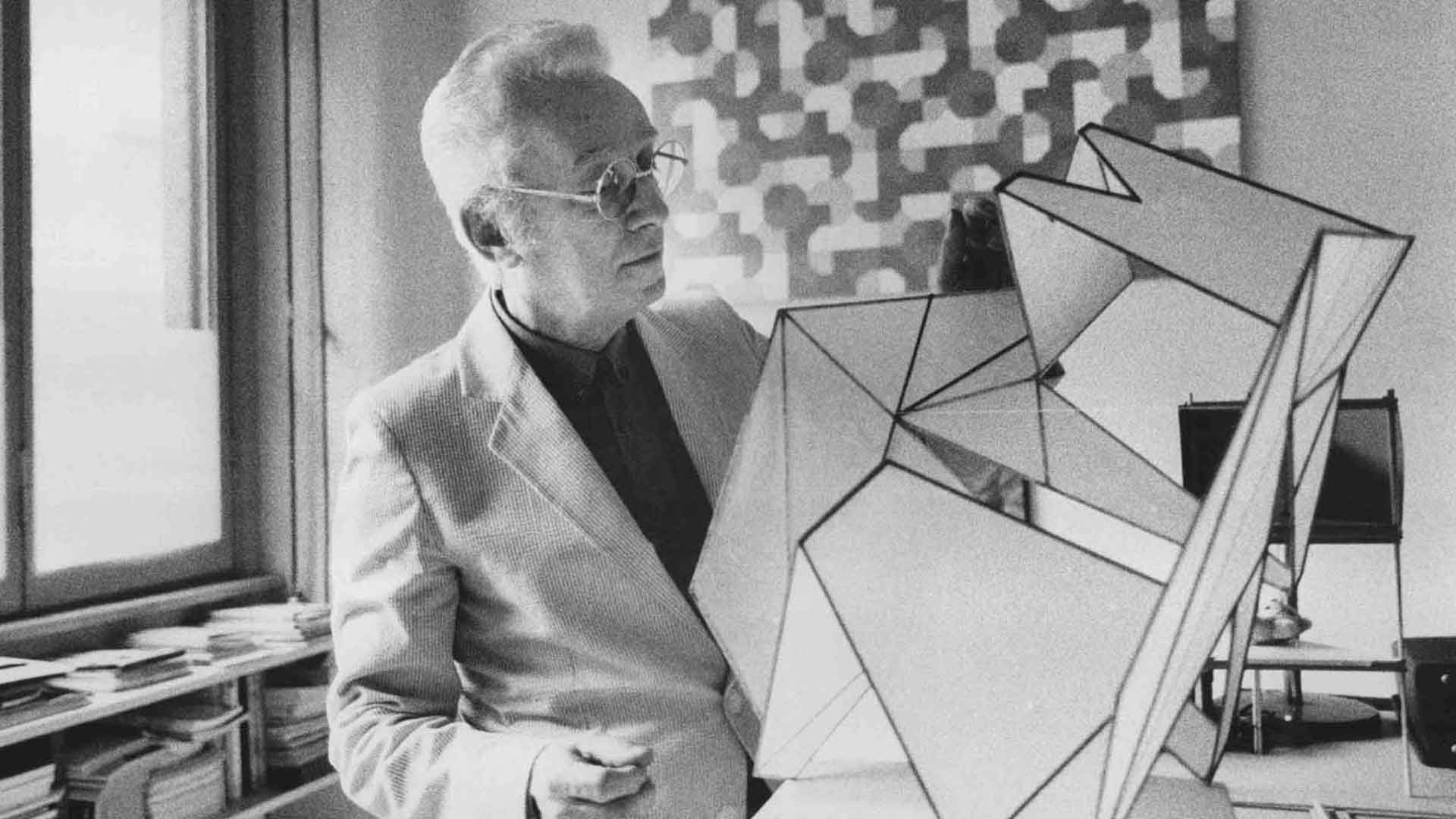

Bruno Munari, Venice 1992, Harmonious Structures

Bruno Munari was born in Milan in 1907. He became a follower of Marinetti and the Futurists in 1927, and during a trip to Paris in 1933 he met the Surrealists Louis Aragon and André Breton. He worked for Mondadori as an editorial graphic artist and art director from 1938 to 1943. That was when he began to write children’s books, which he originally devised for his son Alberto.

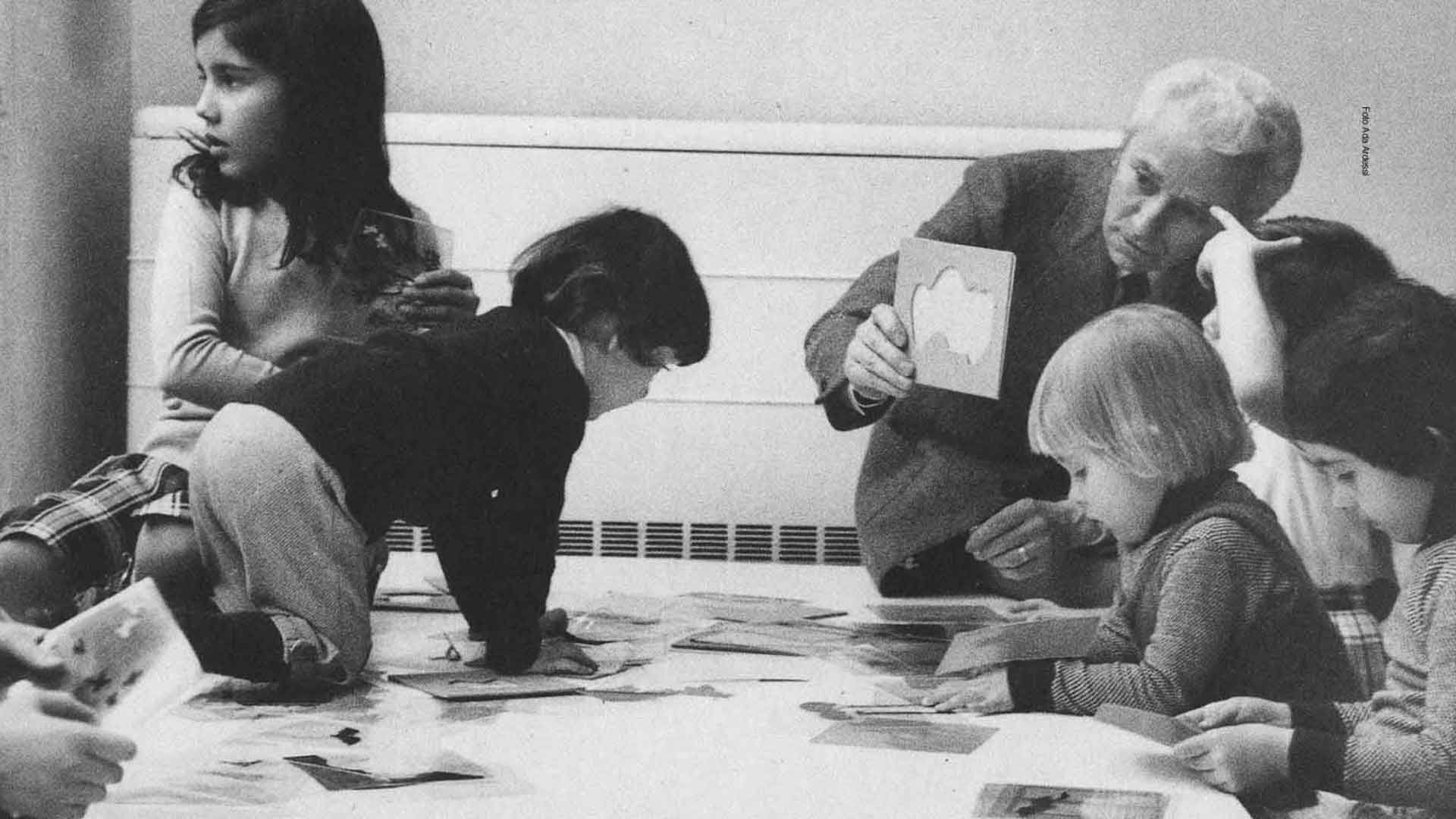

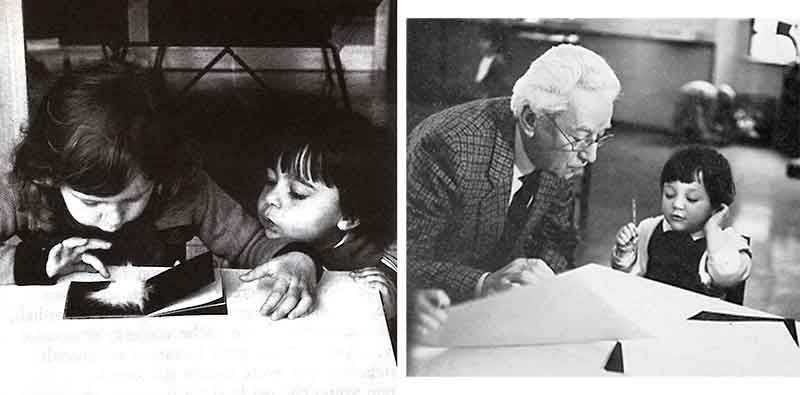

In the 1970s, as Brera was going through a particularly vibrant period in its history, Bruno Munari worked with Franco Russoli to create a series of innovative educational workshops for children that were presented in the Pinacoteca itself.

There is always some old lady who addresses children by making frightening faces and talking rubbish in an informal language full of gobbledygook. Children usually judge such people, who have grown old in vain, quite severely. They do not understand what they’re on about and so they go back to their games, their simple yet very serious games.

Bruno Munari

WORKSHOP FOR CHILDREN

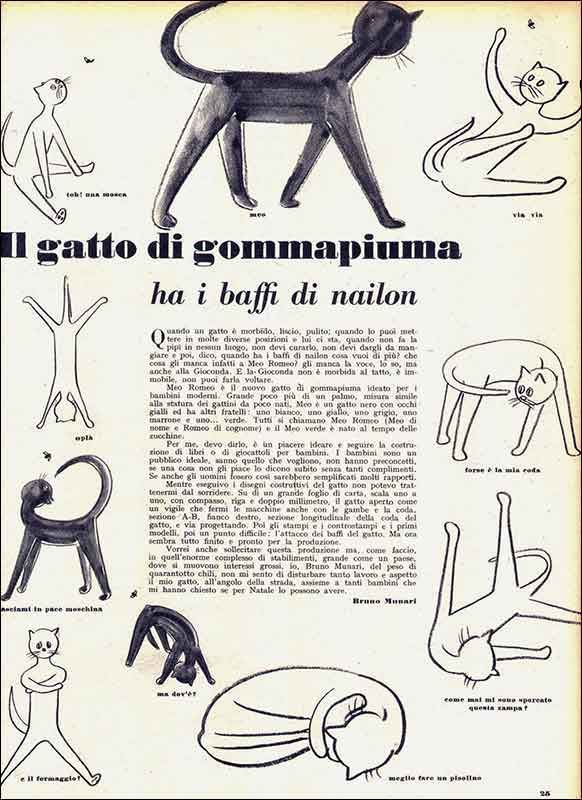

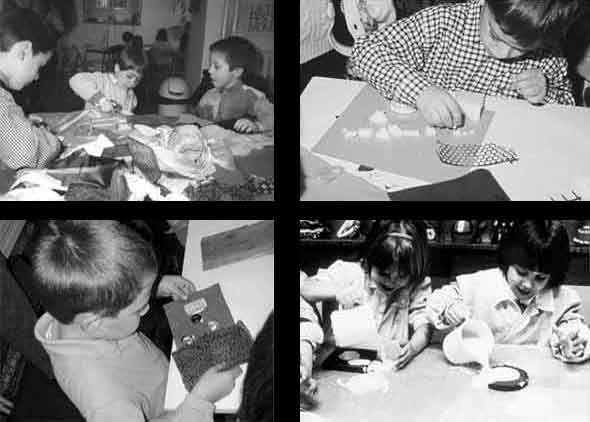

With the support of the Friends of Brera, Munari set up a workshop where children could play with structured materials such as colours in paste form, in slabs, in powder, in blocks and with coloured lights.

While developing the initial project, Munari wrote:

“One hundred thousand visitors a day is not a success for a museum. All these people represent is a figure. Not all visitors to a museum are capable of seeing the works […] because their education is based primarily on literature, [visitors] seek a story in visual art and do not ‘see’ because they do not know the problems, the rules of all that imparts substance to a visual work of art. […] And given that it is virtually impossible to change an adult’s way of thinking, we are going to have to turn our attention to the children. […] If we are worried about changing society for the better, we are going to have to concern ourselves with these individuals who are already here with us.”

Munari also specified what should NOT be done in the workshop:

• Do NOT cause confusion; each topic, each technique, each rule must be visually explained, one a time, each one clearly separates from the other;

• Do NOT explain in words those things that you can explain by setting an example: instead of using words to explain how many ways there are of using a felt-tip pen, take the felt-tip pen and show them how many different kinds of marks you can make with it […];

• Do NOT force a child to do an exercise: if you do the exercise yourself, he will want to try immediately, there will be no need to force him to do it;

• Do NOT criticise or correct children’s work;

• Do NOT throw anything on the ground, litter goes in the dustbin;

• Do NOT dirty anything, or dirty it as little as possible: children do what they see adults do;

• And more than anything else, NEVER suggest to children the subjects of their drawings

Renate Ramge, Umberto Eco’s wife, was one of Munari’s principal assistants at the Brera and she recalls that the educational workshop:

… sprouted in an arid, totally arid desert as devoid of children as it was of artistic education. It was a revolution, and it had the virtue of extracting elements of art that could draw people closer.

Alessandra Montalbetti, who currently runs the Friends of Brera’s education department, cooperated with Munari in the workshops when she was a young woman, and she has fond memories of the experience:

In 1977 I remember that Bruno Munari used to repeat an old Chinese proverb like a mantra: ‘If I listen, I forget; if I see, I remember; if I do, I understand’ and he would force us to listen to the children and to work with them, putting ourselves at their height – which meant squatting, lying down or sitting on the ground, in a Pinacoteca di Brera that was still an ivory tower reserved for art historians and erudite adults. It was a very new experience for us because we did not talk about a painter’s name or his history or the title of a painting and its century, it was as though the painting was being experienced as something living and relevant to the present day. The children discovered the lines and colours that captured their imagination, not reproducing the whole painting but drawing lines on sheets of paper and cutting out shapes that would reconstruct the picture. In our collages we used various fabrics and materials with which the children, and we ourselves, discovered for the first time that we had fingers and what our fingers felt. It was the first time in an art museum that people were using not just their eyes but their whole body.

In 1981 I remember the tensile structure erected in the Loggia on the first floor. It was an area outside the Pinacoteca where a number of students from a class, using fabrics and ‘stage props’, were getting ready to play the characters in a painting such as Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus or Tintoretto’s Discovery of the Body of St. Mark. The rest of the class was involved as directors and set designers, juxtaposing the child actors’ gestures, and making changes to the set; when the painting was similar, not to say identical to the original, changes were made to study the children’s reactions; a light in a different place, a stronger light or a different expression were enough to prompt a reflection on their feelings.

The workshop, which ran from 15 March to 30 April 1977, was an enormous success. Unfortunately, Franco Russoli died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-four on 21 March 1977, only days after the workshop opened.

MUNARI’S WORK

Pablo Picasso called him a contemporary Leonardo da Vinci, and he did indeed produce an enormous artistic output, shown at over 200 one-man shows and 400 collective exhibitions, that was surprisingly varied in terms of technique, method and form.

His work is immense and it cannot be summed up in only a few lins. Here are only a few of his creations:

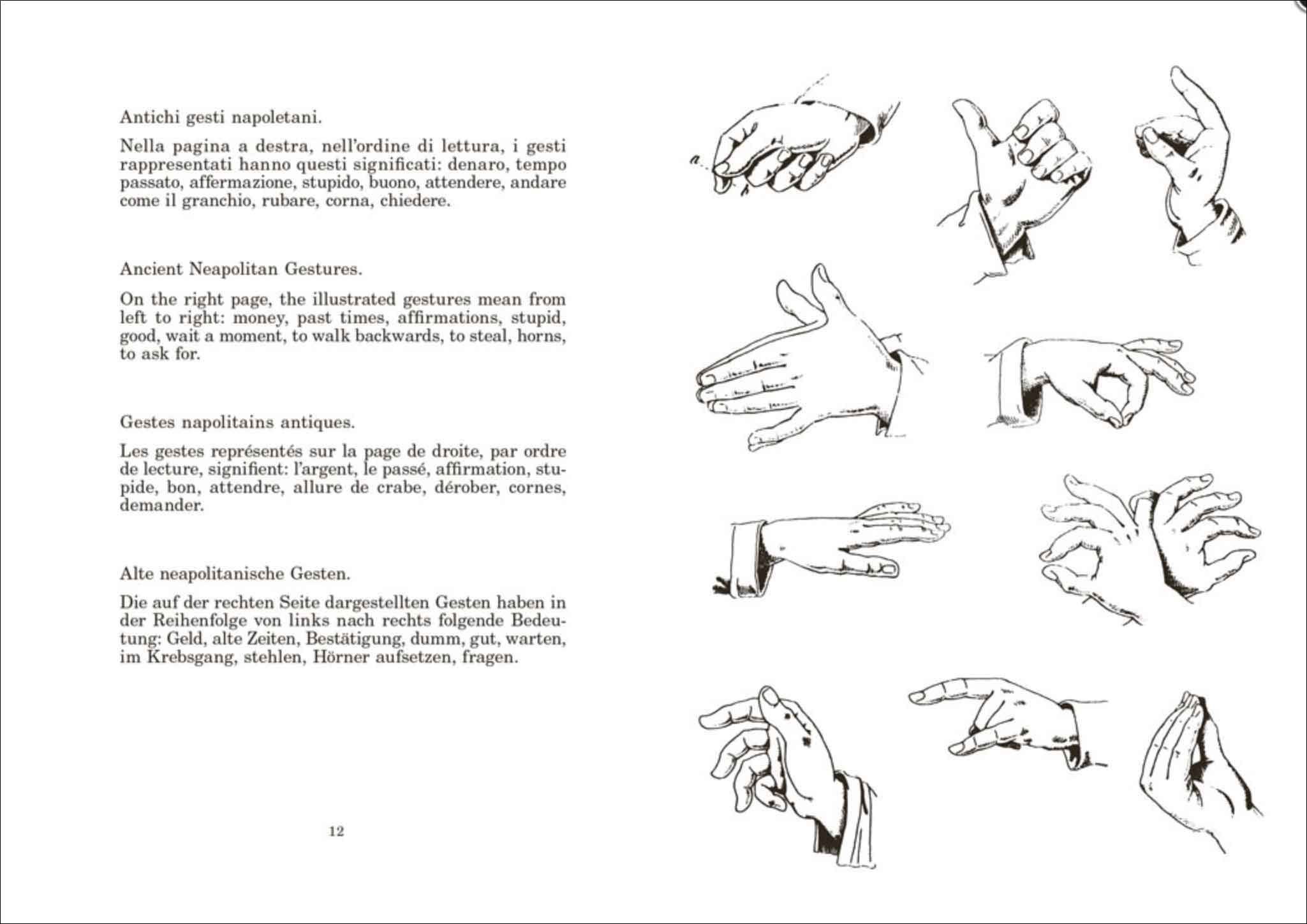

SUPPLEMENT TO THE ITALIAN DICTIONARY – MUNARI AND THE LANGUAGE OF GESTURES

Bruno Munari had a deep interest in the use of gestures in everyday language, a phenomenon that is particularly striking in Naples. In his illustrated book Il Supplemento al Dizionario Italiano [Supplement to the Italian dictionary] published in 1957, Munari examines the various ways in which people express a concept without speaking, not just with their hands but also with their facial expressions and their body language.

The introduction states:

[...] As time went by and the Neapolitans began to travel, many of these ancient gestures became common throughout Italy and some of them are even understood in many other parts of the world. Latterly some of the gestures used by other peoples in the world, like the famous American O.K., have become universally understood, which is why we thought it would be a good idea to collect as many of them as possible, apart from obscene and vulgar ones, to have as accurate a record as possible for foreigners visiting Italy, or as a supplement to the Italian dictionary.

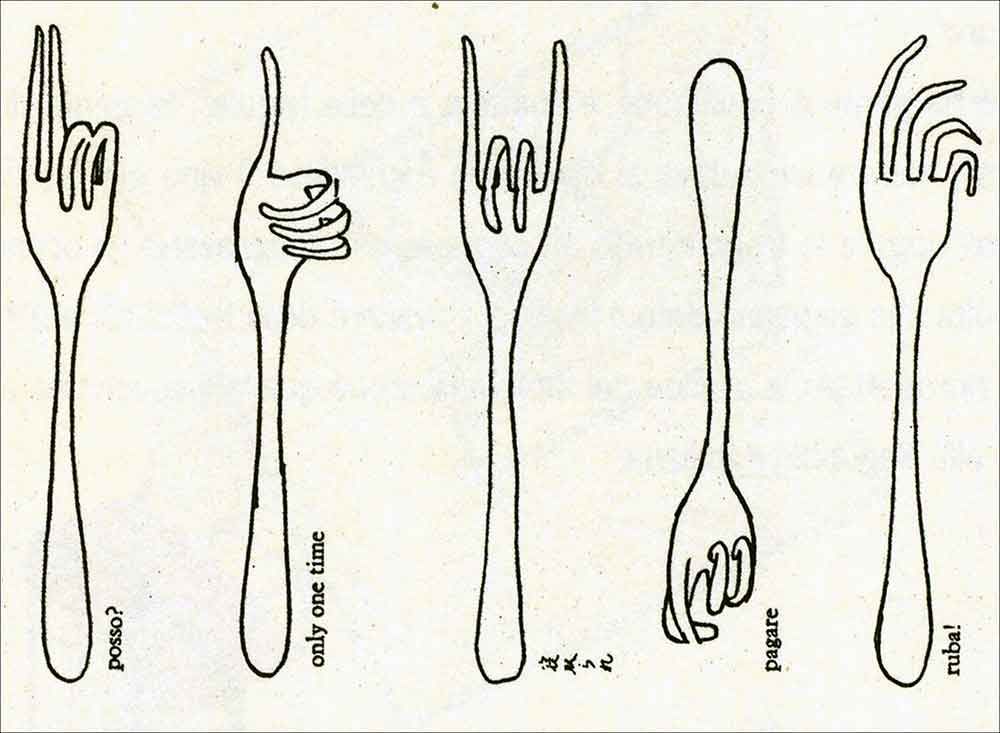

MUNARI AND THE FORK

The hand plays a crucial role for Munari in his capacity as a pedagogue, a writer and a designer, and so he discovered the entertainingly anthropomorphic side to the simple fork.

Luxury is the display of uncivil wealth that sets out to impress those who have remained poor.

Bruno Munari

Every object can have two aspects. A fork, for example, can look like a hand and adopt all the positions of a hand. Munari used up all the forks in his house to prove it, conducting a variety of tests. Here are the best among them:

Bruno Munari, Venice 1992, Talking Forks

Immagine in apertura di Bruno Munari © Giliola Chisté, courtesy Corraini Edizioni