Since the Library of Congress began digitizing the photographs of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), it has blazed a path back into the US of the 1930s and 40s. The 170,000 photographs that make up the collection surprise and complexify by preserving the look of everyday life back in the era of the Great Depression and WWII.

Folks at Yale have unveiled an interface to the FSA photographs called Photogrammar that facilitates browsing the massive collection by county, using a map that arranges the entire archive by locale. Another map allows users to find all images created by a particular FSA photographer, whose shoots show up as dots plastered across the US. (One can follow John Vachon’s photographic odyssey from Chicago across the Southwest to southern California, for instance.) Every photograph in the interface links back to an original Library of Congress record.

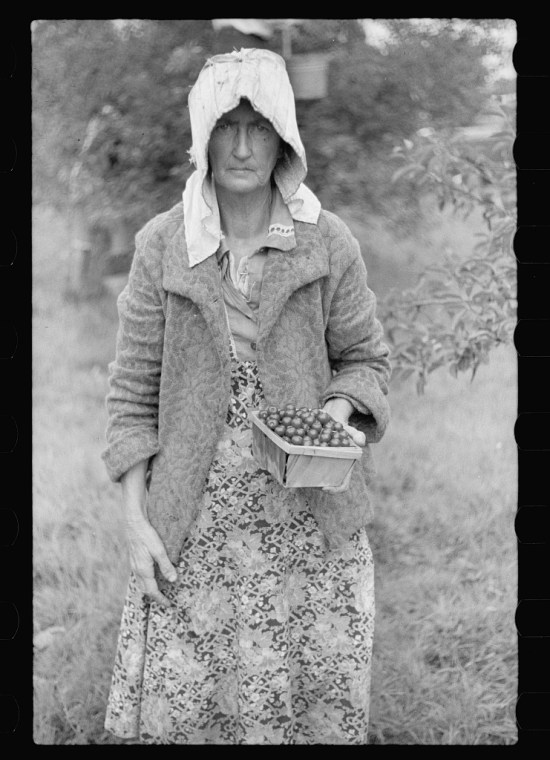

The photograph above is one of many documenting the lives of migrant workers in Michigan’s Berrien County in 1940. Who knew that placid Berrien County (now a Chicago-area vacationland) had its own Grapes of Wrath story? That, in the forties, poor families displaced by the Depression and Dust Bowl migrated up to those parts to pick the fruits and berries that even now are a mainstay of the state’s agriculture? Some 190 photographs by John Vachon record the heart-breaking conditions that awaited those who, after losing their own farmland, had to resort to working as seasonal day laborers. Pictures from the series document the labor of parents and their small children in the fields, as well as their ‘home life’ in the tents and trucks that sufficed as their dwellings.

The FSA photographs document both the nation’s suffering and its dynamism and vitality, furnishing an often startling yardstick of change in the ensuing 75 years’ time.

Image: John Vachon’s “Migrant berry picker from Arkansas,

Berrien County, Michigan” (July 1940),

from the Library of Congress via Photogrammar.

Click here to visit the Photogrammar site.